An interview with Ken Nolan

Dec 21, 2022

Ken Nolan co-wrote this year’s critically acclaimed drama Only the Brave, which examines the tragic Yarnell Hill fire that occurred in Arizona in 2013, and which claimed the lives of 19 out of 20 “hotshot” firemen. Nolan also wrote the screenplay to Ridley Scott’s iconic war film Black Hawk Down, and also worked with director Michael Bay on Transformers: The Last Knight. Back to the Movies’ Nick Clement spoke with Nolan about his fascinating career, telling a true story as intense as Only the Brave, working on films that never get made, what his favorite movies are, who he looks up to in the industry, and so much more.

What’s the first movie you have a conscious memory of seeing on the big screen?

Nolan: I remember seeing Bambi and being terrified. The beginning of the story is very disturbing. I think it was the Hamburg, NY cinema, with red velvety seats and that sound system that sort of echoed all over the place – probably because it was just a few speakers near the screen.

Which films did you grow up with? Did you watch the same movies over and over again?

Nolan: I forced my Dad to take me back to The Towering Inferno after we saw it once, and he grumbled and didn’t want to go, and couldn’t really understand why I wanted to see it again. But he took me. That cemented my love for movies, and it’s something my Dad and I have always shared, which is nice. James Bond movies were always a big deal in our family. I can distinctly remember the agony and jealousy of not being able to see Live and Let Die because I had the chicken pox, and my two brothers got to go without me. I later saw it in a drive in. Drive-ins, by the way, were a huge part of making me a fan of movies, because it was a family event. You drove out to a Drive-in and the kids were in our pajamas, and you got to watch the first movie with Mom and Dad, and then they told you to go to sleep for the second one. But we’d open our eyes and see little snippets of movies like Everything You Always Wanted to Know about Sex (But Were Afraid to Ask), which was in 1972. I remember seeing David Cronenberg’s They Came From Within [aka Shivers] at a drive in and being completely disturbed. Was this how adults acted? Was this what I was in for as a grown-up? It looked scary and confusing and disgusting. So that second movie in the drive-in was always the harder-edged, racier movie, and I really wanted a glimpse of those ones. I think we saw Food of the Gods and very poorly made genre movies at Drive-ins as well. Ben,Willard, those kinds of things. My brother Matt and I went to see Watership Down 11 times, and the animated Lord of the Rings 13 and a half times. I remember seeing The Empire Strikes Back 10 or 11 times in Portland, Oregon, forcing my poor little brother to sneak into line so we could make it into the show. I saw Raiders of the Lost Ark at least 12 times. Once we just stayed and saw it twice in a row, hiding from the ushers in the interim.

Who are your creative inspirations, and why?

Nolan: At first I was really swept up by George Lucas. Need I explain how impactful Star Wars was on an 8 year old kid? It literally blew my head off. I had no head for years! Gone. Then Raiders really cemented my love for giant scope movies. So, Spielberg and Lucas were the two guys to open my eyes in a way that hadn’t been done before. But before any of this, my mom had HBO long before anyone else I knew had it, and my brothers and I would just watch whatever happened to be on. So I became a little tiny walking film library, and I got used to seeing movies over and over again, which I think did something educational to my brain. I really loved horror and genre movies, and I loved James Bond films. It was only later that I started to explore other decades of filmmaking, like the 70s, which is my favorite decade for movies. I remember watching North by Northwest on HBO and feeling sort of annoyed that this OLD movie was on. And it was awesome. From the first moments it was amazing. Something shifted after I saw that movie, because I thought any movies that have been made before my time must be bad. And they weren’t. They’re classics because they’re hugely entertaining. So my interests started going backward, and I began renting videos from whole decades I’d never seen.

As you got older, which films did you gravitate towards?

Nolan: Later I discovered films like Apocalypse Now, The Exorcist, The French Connection, The Conversation, Chinatown, and movies like that, which inspired me to change my thinking about movies. Movies could be spectacles, like The Towering Inferno, but they could also be dark and twisted and have messed up main characters who don’t always win. That was nice to learn.

How did you get into screenwriting? What was your path?

Nolan: When my dad sat me down my sophomore year in high school and asked what I wanted to do, I told him: “I’m going to be a Hollywood director and make a million dollars.” He roared with laughter, thinking I was joking. I think he saw in my face that I was serious, and his laughter really hurt my feelings. So he said, “Okay. That’s good, but don’t you think you should go to college, first?” I thought that was good advice, and hadn’t considered it. But I still was sure I’d be a big Hollywood director. I just didn’t know how to go about it. In college, I was writing short stories and wondering what I was going to do, how I was going to get into the film business. UCLA and USC Film School both turned me down, so I was depressed and despondent up in Eugene, Oregon. During my second year of college there my friend said, “You love movies, you love to write. You should try writing movies.” It never occurred to me before! This obvious path was right in my face. So I really started to study how these people like Shane Black were selling spec scripts. I thought I could sell one. Suddenly I wanted to be a screenwriter.

When did you move out to Los Angeles?

Nolan: I moved to LA after finishing school at Oregon, and got a job as an assistant. First at Richard Dreyfuss’ production company which was at Disney, and was where I learned how to read scripts and how they were crafted. I read a ton of scripts. The Shawshank Redemption really blew my mind. “Oh, that’s how you do it,” I thought at the time. I also realized that reading really awful scripts taught me what not to do, and might’ve been more valuable than studying great scripts. Anyway, I had two friends who were trying to get into film as well, and we’d all read Chinatown and things like that to study how great screenwriters did what they did. Syd Field’s “Screenwriters Workbook” was my Bible. It was underlined and dog eared and worn out. I did everything he told me to do in that book, and that’s how I learned to write screenplays.

When did you find time to write while working as an assistant? I’ve worked as an assistant in the past. Those are some long hours.

Nolan: I would write scripts after everyone went home from Dreyfuss/James Production Company, in the Animation Building at Disney, because they had a computer and I didn’t. The cleaning lady would come in and vacuum around me as I typed and had my dinner (two tacos from Taco Bell). Anyway, I wrote a bunch of really awful screenplays and got a job as an assistant at another company. I was 26 and feeling like it was too late for me. I had missed my chance. I was TOO OLD to make it. My girlfriend was my boss at the time (don’t ask), and she sent my latest script to an agent friend of hers, named Larry Kennar. Larry sold my first script to Matt Leipzig at Jerry Weintraub’s company at Warner Brothers in 1994. It never got made, but I had sold my first script. I was in! The rest would be easy, right? RIGHT? Cue the spooky music…!

What do you consider to be your “big break” in the industry?

Nolan: My first real “big break” was the sale of my second script, The Long Rains, which Imagine bought. That really cemented that I could actually write pretty well.

What’s “The Long Rains” about? The title sounds ominously cool! Why didn’t it get made?

Nolan: It’s about a guy who breaks out of prison during a huge flood somewhere in the south, and heads back to his home town to find the money he’s hidden from a bank robbery, only it’s under all this water now, and the local Sheriff wants to kill him, and his ex-wife wants to kill him, too. Very film noir kind of thing. John Frankenheimer was attached to direct, and Imagine had bought it. It was FOR SURE going to get made! Whee! Then, of course, it fell apart. John called me and said, “I’m just so sorry about this, Ken, but I don’t think they want to make your movie anymore.” John turned out to be a huge influence on me anyway, in that short period of time. I still think about him every once in a while. He was a force. And, I made lifelong friends from Imagine. We still have lunch twice a year and talk about all the memories of that time. It was the 90’s, when spec scripts went out on Tuesday, and if you didn’t have a bid by Wednesday, you were dead. But you could sell things in 24 hours, too. It was an amazing time in the film business. Oh, but anyway, another film started getting made that ended up being called Hard Rain, by Graham Yost. So that was that. Oddly, Mikael Salomon, the director of Hard Rain, would later direct my TNT mini-series The Company.

Wow! The industry is such a small world sometimes. And while we’ll certainly get into “The Company” in a bit, I’d love to hear about how you got the job working on “Black Hawk Down,” and what that did for your career, and your mindset as a screenwriter?

Nolan: I had gone on a meeting at Disney, one of these general meetings, and Todd Garner told me they had this book in galley form, which Jerry Bruckheimer was going to make. It was called “Black Hawk Down.” I had no idea what those three words meant. It was tantalizing. By this time I had sold a third spec script, so I was fairly established as this guy who sold a few scripts, but I still had no movies made. I was desperate to get something made. I read the book in one or two “sittings,” which was me lying on my couch, sweating and wide eyed at Mark Bowden’s second by second account. I had never read anything like it.

What was it like meeting at Jerry Bruckheimer Films?

Nolan: My agent set up a meeting with Chad Oman, who is one of the big executives at JBF. We met for a beer at the Bel Air hotel, and I stumbled through my pitch of how I saw the film. It was about five minutes of me talking, and Chad staring at me in his unnerving way. Then he said, “Okay. I’m gonna get you into this.” I had the job, basically. I was so excited. Then a long, long time passed. Something like six months, as they waited for Mark Bowden to adapt his own book into screenplay form. I didn’t know this until later, but they sort of knew Mark wouldn’t get the screenplay format on his first try. Mark will tell you himself, “It was the worst screenplay ever written.” So here I am, waiting, not knowing the reason for the delay, and they finally say, “Okay, come in and meet with us and Jerry.” I already knew Mike Stenson at Bruckheimer Films, and he liked my writing. I had never met Jerry Bruckheimer. Also, Simon West was there, because he was attached to direct.

Wow. That’s a helluva room to be in!

Nolan: I was REALLY nervous. Like, almost unable to speak, nervous. But Simon and his producing partner Jib Polhemus were so cool and laid back, and Jerry turned out to be such a gracious guy, that I sort of got over the nerves, and we started talking about how to adapt the book. I suggested I do a very detailed “scriptment,” a treatment with dialogue and scene description. I had seen this from a laser disc of Aliens, where they had a copy of Cameron’s scriptment for Aliens. I read that and said, “Oh! That’s a great idea. You don’t write the script, you write a treatment first, and work off that until you get it right. Then you write the script.” That’s what we did. We did three of those, and Jerry said, “Ken, I think you’re ready to go write the script, now.” So we did a first draft. I ended up doing about 12 more drafts after that.

Initially, as you mentioned, Simon West, who had done Con Air for Bruckheimer a few years prior, was attached to direct. What happened there?

Nolan: Poor Simon had to go off to direct Tomb Raider and he regret

s to this day that he didn’t get a chance to direct Black Hawk Down. But then Ridley came into the picture, and the rest is film history, dare I say. When Ridley came in, he was the reality police. He taught me to write with subtlety and to downplay the “movie-ish” writing that I had sort of trained myself to emulate. I learned more in that year with Ridley Scott than I had in the previous ten years of trying to write screenplays. Writing for Ridley was like doing my PhD thesis on screenwriting. I don’t know what I had been writing before that, but he completely changed my style of screenwriting.

And then they brought in some other guys – some very “big” guys if I’m not mistaken?

Nolan: Ridley, I guess, wanted another writer to come in and rewrite me. So they hired Stephen Gaghan, who had just blown up after Traffic. He came in and was quickly let go, but to me the damage was mentally done. I was shattered. I didn’t understand why I wasn’t good enough, what I had done wrong. I just didn’t realize this was the movie business. I was pretty crushed. In my perspective, I was going to stay with this movie all the way through, and now that was yanked away. “Thanks for your work, little writer, now the real writers come in,” is the thought that was playing in my head. Jerry, Chad and Mike were all very kind about it, and knew it stung me a lot. They said, basically, “Hey, you took it where you could, and we just want other really talented people to help.” Now, of course, I see the logic in this. At the time, I pouted and complained like a little baby. So, Gaghan was shown the door after a few months. Ridley had just worked with Steve Zaillian on Hannibal, and he wanted him to come in to do “about six weeks of work” rewriting me.

But then you came back to help out again, yes?

Nolan: About four months later, this was maybe January of 2001, Mike Stenson and Chad Oman called me, furious. “Why aren’t you answering your phone?!” they asked. I said “Jesus Christ, man, I was watching a movie at the Beverly Center! Why are you mad at me?” I think I had seen Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, which is a long movie! Well, they said, “The Steve experiment is over, and we need you back!” They had just received Zaillian’s script, and were very, very concerned. I was both excited and terrified. I was supposed to rewrite the Academy Award winners’ scripts? Were they nuts? Chad said, “Get your passport, buy a laptop, and bring all your notes with you. You’re going to Morocco to work with Ridley to make this script better. Oh, and by the way, the movie starts shooting in a few weeks.” The next five months changed me forever. Ridley really took me under his wing, and taught me how to write. I realized that I was still so green and immature and uncertain about my writing. Working on set with actors, with Ridley and Jerry and Chad and Mike, was what made me the writer I am today.

After Black Hawk Down, did you do a lot of uncredited re-writes, or write specs which were sold and then didn’t get made? I always presumed you became “one of those guys” who gets paid the big-bucks to do “clean-ups” and “polishes.”

Nolan: Black Hawk Down was finished filming in August, I think, of 2001, and they didn’t release it until the next year. In that time, I didn’t have a job. I was sort of waiting for my career to take off, like everyone said it would. I assumed I would get those big rewrite jobs, like Gaghan and Zaillian. Those opportunities never happened. I never did any of these big rewrites. In my opinion, they are newsworthy because they are infrequent. To me they’re like the Easter Bunny. They don’t actually exist. Sure, big shot A-listers did them, but until Black Hawk Down came out, and even afterward, I still had to hustle and prove myself. So I wrote more spec scripts. I wrote a scriptment for something called The Forge of God. My now third agent, Todd Feldman, sold it for a life-altering amount of money. I was set! This movie was GOING TO GET MADE! Right? They spent so much on it, they had to make it. Wrong. I worked on that for a couple of years and it finally just went away. I adapted a book called The Proving Ground for Paramount. It’s a great book about the tragic 1998 Sydney to Hobart yacht race. It was like The Perfect Storm times 100. We almost got that made, with Phillip Noyce directing. Phillip would let me and my wife stay at his place in Sydney as I did research. Lynda Obst was the producer, and she taught me a lot as well. We got really close to making it, but then it went away….lost to the ages….cue the sad music.

I often envision this little fantasy land of unmade projects just waiting to finally get made. It’s sad when this happens. What does this do to you as someone who needs to create in order to feel fulfilled – writing something and then not seeing it on the big-screen must be extremely disappointing?

Nolan: As my agent would say, “Kenny! Uptown problems, Kenny. Uptown problems.” But they’re my problems, and you asked, so I’d love to bitch about it a little. It can be very demoralizing to work on something for years, and to put your heart into the writing, and do a dozen drafts, and then just have it go away. Gone. No one even wants to TALK about it after that. It’s like an Uncle who went to prison for child molestation. “You don’t MENTION UNCLE HAROLD IN THIS HOUSE, do you understand?” I liken it to being a painter, and working really hard on paintings I’m very proud of, and that I think are the best I can do – and these paintings never get seen by anyone. They go into the garage. After a few years, there’s like 20 of these massive canvasses collecting mold and mildew. Never to be seen. EVER. And then I get people sort of innocently asking me, “Why don’t you have more movies made?” I want to take those people to the garage and sort of mumble, “Here they are.” Then shove them inside and lock the door, shouting, “Enjoy! ENJOY THE READING!” As you can see, I’m a bit unhinged when it comes to this topic.

Ha! Passion is what drives us, and it’s clear you have tons of that. How did you get involved with working on The Company?

Nolan: I think it was 2004, John Calley hired me to adapt Robert Littell’s doorstopper novel The Company. John was one of these guys, like Ridley, who really shaped my career and perspective in the movie business. He was just a classy, funny, laid back guy. He waited politely for my script for four months. “How about this, pal? You give me a page a day to read,” he said at my office door once (he had given me an office in his place on the Sony lot), “and I’ll read it, and it’ll be like ‘1001 Nights.’” I finally finished the script in 2004. He loved it. He asked me to call Ridley and ask him to read. Ridley did, called me and said, “Ken, I want to do this next.” We were on! We were making this film! Ridley’s team scouted locations, Columbia spent $250,000 on pre-pre-production stuff, and then Amy Pascal pulled the plug.

Why? What happened?

Nolan: Eric Roth’s genius script The Good Shepherd was finally being made, and it was too similar. I remember calling my wife in tears. I was just so frustrated that none of my screenplays became movies. So, after The Company died as a feature I was really depressed and wondering what was next. Would I ever get a movie made again? There were job offers, but I turned down everything. I’m just not that guy who can work on something without really loving it.

But then it got made as a mini-series – which I absolutely loved!

Nolan: Thank you! Ridley promised to do it someday, and we eventually made it at TNT as a mini-series, thanks to Michael Wright, who always loved the book. Ridley called me and said, “Ken, we’re going to make a mini-series. I’ll produce it. It’s too good to let go, Ken. It’s too good.” We had a meeting with Michael Wright and others at TNT, and they asked if I had any extra pages from my feature script. I laughed and said, “I have about 300 extra pages!” They loved that. So David Zucker at Ridley’s company, and Ridley and John Calley and I all worked to make the three-part, six-hour version. Then Mikael Salomon came on to direct, and we got along great. We did a few drafts of the script, little “Bits and Bobs,” as Ridley would say, and then we made the show, filming in Toronto, Budapest, and Puerto Rico. It was a very gratifying experience. Then I won a WGA award for it! Totally unexpected. What a great time that was.

I gather you wrote a script that was based on Whitley Strieber’s “The Grays” – what happened with that project?

Nolan: A producer named Cary Brokaw brought me Whitley Strieber’s The Grays, which is a terrifying, brilliant novel about aliens. I loved it. It just had no third act as far as I could tell, but I thought I could do it. Whitley was very supportive about trying for a big alien battle in the third act. “Go for it, Ken,” he emailed me. So I wrote another scriptment, and my insanely talented agent sold that one, too! ANOTHER FORTUNE! Sony bought it! They spent so much money, THEY HAD TO MAKE IT! Right? Right? Cue that spooky music again right here…Well, it didn’t get made. I spent a year or more doing development. Wolfgang Peterson finally came on to help me do a radical pass on the script. That didn’t work out, either. Wolfgang was very depressed for us both after that. “Ken, I tell you, this is one of the worst days I’ve ever had in this business, being told we aren’t making this movie…” So, to answer your question about why I haven’t had more credits – it’s not for lack of trying. It’s just incredibly hard to get movies made. You wonder why I don’t have more credits, and I wonder how people like David Koepp, Steven Zaillian, and Akiva Goldsman have SO MANY credits. It’s amazing to me.

What happened after The Grays fell apart?

Nolan: After The Grays went into a huge warehouse of unwanted screenplays in some underground bunker in Iceland, I was again wondering if I would even have a career. At this point, I was REALLY expensive. I had sold big spec scripts. They didn’t get made. I think people wondered, “Why hire Ken for anything? He doesn’t get stuff made and he costs a lot.” I started doing two projects for Mike Medavoy and Brad Fisher at Phoenix Pictures, for scale – about $40k for each one. But I was their producing partner, and the rewards could be huge if we made the movies. Jamie Vanderbilt had just done something like that with them on “Zodiac,” and I was excited at this prospect. Mike and Brad were both great to me, and we worked very hard on Koko, a Peter Straub book I’ve always loved, and Anvil of Stars, which was a sequel to the unmade Forge of God, by Greg Bear. Warner Brothers agreed to let Brad and Mike have us try to salvage Forge of God by making the entire movie a sort of 15 minute prologue to Anvil of Stars. These movies, at long last, would be the ones to get made. RIGHT? RIGHT! I think you know where this is headed…

How did you come to work on “Only the Brave”?

Nolan: Producer Jeremy Steckler had been sending me articles from Conde Naste, and I turned down two or three. Then he sent me the GQ article by Sean Flynn, and I said, “Shit, I can’t turn this one down.” It wasn’t the whole story, so I knew I’d have to interview people and pry into a very painful experience, and I wasn’t sure I was up to it. I’m not a reporter. I had never really done much work like that. I agreed to do a script on spec. I had no idea if we’d sell this, or if I’d get paid, but I knew if I did on spec, with these producers, I’d be in good hands. And we would control it. Not a studio. I had been down that road about 10 times, and look how it turned out. No movies made. A great career, lots of money in my bank, and satisfaction there, but no movies except for one. I was driven to write something that was important and meaningful. Something that would get made. Lorenzo diBonaventura was the producer, and Scott Cooper was attached to direct. We didn’t know if any of the wives or mothers or sisters or brothers would talk to us, but our other producer, Mike Menchell, had already made headway with some of the people in Prescott, Arizona, including Amanda Marsh and Brendan McDonough. Lorenzo suggested that Mike and I go to Prescott and start talking to them. At this point no one knew what the story was. Was it this big fire that killed the squad? Was it the story of the Granite Mountain Hotshots becoming who they were? Was this a disaster movie? Lorenzo and Scott both leaned toward something like The Perfect Storm, showing the characters and what these guys did, getting to know them before they were suddenly taken away from the viewer.

The process of writing films that are based on true stories, especially ones that are tragedies, is a delicate and tricky thing to pull off. How did you approach this fact?

Nolan: Scott Cooper really gave me a good speech about not writing a “movie,” in so many words. He told me not to write the way I was used to. Let scenes play out, he said. Don’t end them when you normally would. Don’t gravitate toward movie conventions. Let dialogue be messy. Let scenes start and end in unpredictable ways. It was great advice. Going to Prescott and meeting Amanda and Brendan was gut wrenching for me. Amanda was rightfully very suspicious and defensive about this story becoming a movie. She looked right at me and said, “Why do you think this should be a movie?” I said, “It doesn’t have to be. But from what I know with ‘Black Hawk Down,’ the world would have never known the story of those soldiers unless the movie was made.” She seemed to take that in and consider it. Amanda Marsh does not suffer fools, and many times in this process, I doubted myself and felt like a fool. But Brendan really helped us. He’s an amazing person. He took us to the big juniper tree, and he took us to the graves of who he calls his brothers. It was extremely emotional for me, but Brendan was stoic. He had been through something I could never truly comprehend.

So how did you find your “in” to the story?

Nolan: Lorenzo and Mike and Jeremy and Scott were all asking me, “Ken, what’s the story, what’s the story?” I said, “I think this is the story of Brendan being the new guy, and coming into a squad that is trying to become Tier One,” which might seem more obvious now, but at the time none of us knew what to do. I said, “It’s about their lives and their families and their work.” They said, “Yes, that’s it.” We all talked for hours about it in several meetings. This was a movie that would show a group of special, dedicated men doing a thankless job, one that is nearly invisible to the outside world, one that only extremely driven young people are capable of doing. And how does that impact their relationships at home? How do wives and kids deal with their dad doing this job, disappearing for weeks at a time during fire season? Lorenzo and Scott and I even talked about NOT showing the final fire. I remember Lorenzo saying, “Maybe the movie ends with the guys saving the big juniper tree.” We really thought about how to handle this story respectfully and carefully. It was also a long process, just like with Black Hawk Down, of knowing we couldn’t tell all 19 stories, but we had to choose a few main “characters,” then two or three supporting guys, then two or three below that group. It’s a long process of trial and error.

Why was the title changed from Granite Mountain Hotshots, to Only the Brave?

Nolan: Sony marketing changed the title, as far as I know. I’m not sure why.

What was your collaboration like with co-writer Eric Warren Singer?

Nolan: I didn’t collaborate with Singer. He was brought in to do “a few weeks of work” on my script, because at the time I was working with Michael Bay on Transformers, and I couldn’t do both jobs. Singer came in and really did a huge rewrite. He wrote every line of dialogue, and really leaned into the characters. He completely changed the Eric Marsh/Amanda Marsh relationship. Amanda never told me about the AA aspect of Eric, and how he saw himself in Brendan. That was all Singer and Joseph Kosinski, who ended up replacing Cooper as director, finding this out and utilizing it. Of course, I spazzed out and yelled and screamed. It was “Black Hawk Down” all over again. Replaced, rewritten. Why? WHY? But you know what? I realize now that I have limits. And producers and directors want different voices and styles. That makes sense to me, with some time having passed. In fact, I just had a great experience with Scott Frank rewriting one of my scripts for Fox. I read the rewrite and sort of said, “Shit, why didn’t I think of any of this stuff?” Well, because I’m not Scott Frank, and he’s not me. So, I can see the sense of having a rewriter sometimes.

Describe collaborating with Joseph Kosinski, who previously has been best known for sci-fi action films, including Tron: Legacy and Oblivion.

Nolan: Scott Cooper dropped out to direct his own screenplay, and we had a void. No director. At this point we had not even tried to sell the script. I was still working for free, just like all the producers. We were gambling we could sell this if we had a director attached. There was talk of waiting for Peter Berg, who Lorenzo was working with on Deepwater Horizon. But it seemed to be taking forever, and I had heard from my agent that Joe Kosinski wanted to do it. Joe is great. We’ve gotten along since day one. He’s represented by my agent, who called me and said, “Kenny, Joe wants to do something else than a sci-fi movie. He read your script and said he’s never had a script this good or realistic that he could direct. He really, really wants to do it.” So I sort of kept pushing the producers. I called Joe and said, “Hey, I really want you to do this, but I’m just the writer, I don’t know if my opinion means that much.” He thanked me, and finally got a meeting with Lorenzo and Mike Menchell and Erik Howsam (Lorenzo’s producer). The meeting was a huge hit and Joe blew them away with his enthusiasm and ideas.

What was your reaction to seeing the full cut of Only the Brave for the first time? Where was this screening, and who was in attendance?

Nolan: Joe showed a really rough cut to me and Claudio Miranda, his cinematographer, at his office in Santa Monica. I was very impressed, and knew that with special effects, music, sound effects, and million little things that go into the movie, that it would be 100 times better. But it was already very good. I cried at the end. It was already that good. Then I saw another screening that Joe invited me to. Again, I thought it was very, very good. THEN – I went to the premiere, on a HUGE screen, with a giant audience, and I think I basically sobbed at the end. Wept. The movie was much better than I thought it was. It was, in fact, great. It was rough and dirty and not “movie-ish” at all. The feeling was the same one I had after seeing Black Hawk Down for the first time. The similarities to this story, and the writing process, are eerily similar.

When dramatizing a real life event, how careful must you remain to the facts, while still acknowledging that poetic license in inevitable and warranted?

Nolan: It’s a tricky thing, and you make decisions as you go through drafts. “You know, we can’t have a whole year pass. We gotta mess with the time of this story,” are examples of ideas you come to after trying different things. I like to stay very, very close to what happened. I don’t want to make things up. But I will play with time, and if something happened to someone who isn’t your main character, but is an awesome moment, I’ll give it to the main character instead, if it works. Like Brendan’s rattlesnake bite. That happened to Pat McCarty, and I asked Pat “Can I give that moment to Brendan’s character?” Pat shrugged, “Sure. Fine with me.” I thought it was a great scene, because Pat had never really bonded with Eric Marsh until that moment when

Marsh showed up in the hospital room to see Pat, and Pat could see how much Eric cared. He couldn’t say it, but he showed it. It was too good a scene to toss out, just because it happened to Pat and not Brendan. So, to answer the question, it’s a long process with a lot of back and forth. For instance, we almost cut out Shughart and Gordon’s story from Black Hawk Down. But Chad Oman insisted it be in there, and he was right. These guys were the epitome of heroes. And because “Black Hawk Down” was so jammed with characters, and because the script was so long, we nearly cut that out. It’s a process….

What’s it like to work with Michael Bay on the most recent Transformers film. Did you experience “Bayhem” first hand? I’ve long been a huge fan of his patented brand of visual mania and I think he’s on another level with cinematic action.

Nolan: That is a whole other interview that could go on for hours. Short version: Michael is awesome, and this is one of those seminal experiences for me in my career, like working with Ridley, that has changed me as a writer and a person. Michael’s work ethic is otherworldly. He busts his ass, all the time. He expects the best from you, and if you’re not giving it, he’ll let you know. The perception of him is all wrong, in my opinion. This guy is an artist who has been treated so poorly by critics that it has become its own perpetually moving machine of negativity. But enough of that. Michael had me and the other two writers come to set in shifts, and we’d rewrite scenes on the spot, with the actors, and we’d toss in lines. He’s collaborative on an insane level. “Ken Nolan!” he’d shout. “Anything else Cade could say here?!” I’d say something and he’d say, “Yeah, yeah, that’s great! Keep going!” He’d egg me on and make me keep rambling, then crack up. “Write that down and print out the pages right now.” We’d shoot the rewrite a few hours later. How cool is that? His sets are full of really hard working people, who are all working diligently to make something huge and amazing. Michael laughs a lot more than he yells, that’s for sure, but he can yell, too. He loves being on set, loves directing, working with actors, shooting his own stuff on his camera. I was there when Arri, I think it is, gave him his very own “Bayhem” Red Camera. He was so excited. He used it throughout filming.

How are Michael and Ridley alike?

Nolan: They are both open to any suggestion you have. Michael might see something cool that he didn’t see a moment ago and shoot it. Ridley would do the same thing. He’d see a tree and say, “Look at that tree over there, mate.” And a little later he’d be filming part of the scene with the tree in it. The craft service guy could give Ridley a suggestion and he’d listen. Michael would ask me what the tone of some scenes were, and he’d LISTEN TO ME! Crazy! It’s a really fun, hard experience, and I miss it now that it’s over. The set does not feel like a huge budget movie, either. It’s kind of small, quiet, and sometimes Michael will just plop down in the dirt with the day’s pages in his binder, directing in his head. You don’t mess with him in these moments. He’s visualizing his shots in those times. And like Ridley, he’s fun when the day is over. Wants to get dinner and have a glass of wine and tell stories. The day’s done, let’s loosen up and have a good time. It’s really about the journey with him as much as the final result. At least, that’s what I think.

What are some of your upcoming projects? What’s Luna Park, and how much more involvement will you have with the Transformers universe?

Nolan: Luna Park was a Doug Liman thing I did a draft on way back in 2008, I think. Another seminal experience working with another big director. Doug has a totally unique and different way of doing things. I didn’t get it at the time. I think I would now, since I’ve matured and grown as a writer, in my humble opinion. We’ll see about Transformers. No one has spoken to me about anything. I’d do it again in a heartbeat. It’s fun writing these huge scenes, and also writing character stuff, like the scene with Izzy and Cade talking about calling Cade’s daughter. “What would you say to her, if you could?” The whole time they’re replacing Bumblebee’s voice box. It’s ridiculously fun.

Is there a particular genre you’d like to explore? Do you have any passion projects?

Nolan: I love grounded science fiction. Michael Crichton is my biggest hero. His stories are plausible and terrifying because they could happen tomorrow. Most of my passion projects are my unmade scripts, like Forge of God, Sydney to Hobart, Anvil of Stars, Koko. I have some specs that have never been bought or made. I would love to direct some of them myself someday.

What’s your favorite movie of all time? Or if you’d like, what are a bunch of your favorite films?

Nolan: Here’s my top ten, and these are movies I’d watch over and over again without boredom: Apocalypse Now, 2001: A Space Odyssey, The Exorcist, The French Connection, Alien, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Star Wars, Blade Runner, Rosemary’s Baby, Blue Velvet, and Out Of Africa (I threw in an 11th because it’s like ordering bagels, you get an extra with the order).

Do you have one particular director, or a bunch of directors, whose work you’ve admired most? Any screenwriters?

Nolan: Stanley Kubrick is number one, of course. David Fincher. I love William Friedkin films, even the bad ones. Ridley Scott, of course. Francis Ford Coppola, both as a writer and director. Franklin Schaffner. John Frankenheimer. Steve Spielberg. I’m into Akira Kurosawa movies late in life. Alan Pakula. Sydney Pollack. I love John Carpenter’s movies. Paul Verhoeven was awesome. When it comes to screenwriters, well, of course Paddy Chayefsky. John Milius. I like David Koepp’s writing, and his career, a lot. Sort of envy and covet it. David and Janet Peoples are amazing writers. Their 12 Monkeys is a masterpiece of a script. I don’t love flashy writers or writers who are saying “Look at me write!” You know who I mean. Don’t you?

Which filmmakers would you like to work with in the future?

Nolan: Sir Ridley, one more time. Chris Nolan, because we have the same last name, and it seems aesthetically pleasing. I think Denis Villeneuve is amazing, even if that’s not the correct spelling of his name. David Fincher, although I think he would scare me. J.C. Chandor I think is really cool and interesting, as is Jeff Nichols. If they resurrect Sam Peckinpah, that would be the ideal director to write for.

Publisher: Source link

Bringing Fresh Life to a Classic Spoof Series

After more than thirty years since Naked Gun 33⅓: The Final Insult (1994), director Akiva Schaffer (Chip ’n Dale: Rescue Rangers, Popstar: Never Stop Never Stopping) resurrects one of comedy’s most absurd and beloved film franchises with The Naked Gun…

Aug 11, 2025

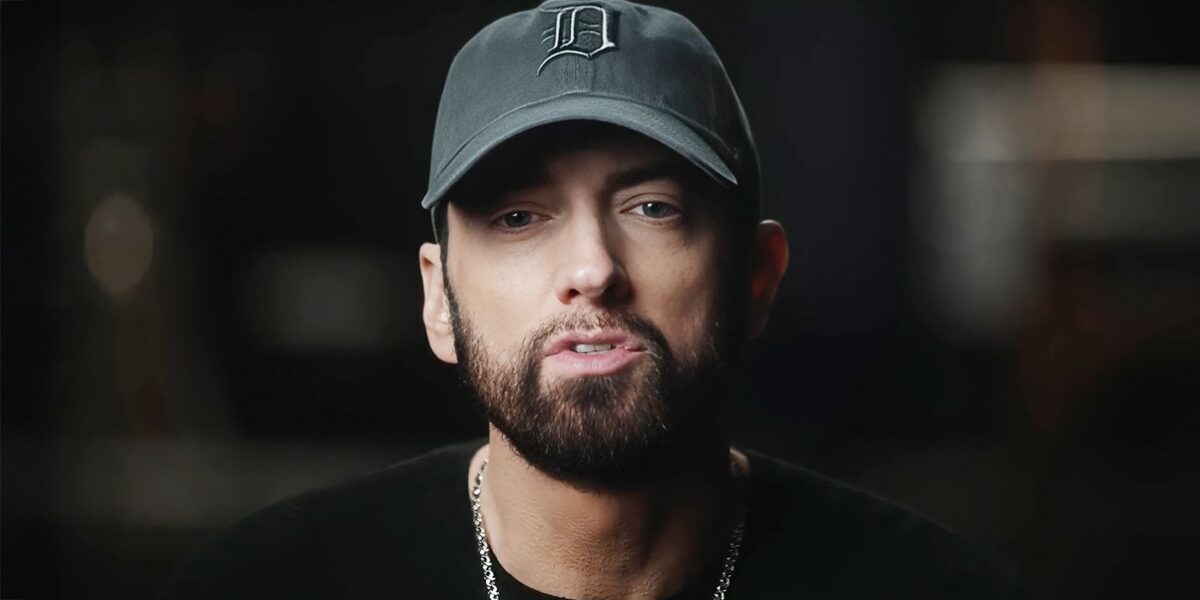

This New Documentary Is a Dark Look at Fame, Fandom, and the Career of Eminem

Fandom is a tale as old as time. For as long as there have been artists, creatives and leaders of any sort, there have been people who admired them and looked to them for guidance on how to live their…

Aug 11, 2025

Zach Creeger Drops Mass Destruction Bombs Of Creepy Terror In Spine-Chilling New Horror

Electric, terrifying and hypnotically creepy af, writer/director Zach Creeger’s latest psychological horror, “Weapons,” dips its toe into the unknowable on many levels. Who are your neighbors? Who are the people in your community? And how can you properly articulate the…

Aug 10, 2025

Buckley’s Life Is Put On Display, Only For The Documentary To Fail To Capture Him

It's Never Over, Jeff Buckley never lets us forget that the man, the myth, and the subject of this documentary, Jeff Buckley, was an unknowable enigma. The feature-length exploration of his too-short life ultimately fails to understand him, despite its…

Aug 10, 2025