Gareth Edwards on the Groundbreaking Way He Shot ‘The Creator’

Sep 28, 2023

The Big Picture

Director Gareth Edwards utilized his experience with independent filmmaking to efficiently use available resources in his latest movie, The Creator. Edwards co-wrote the film with screenwriter Chris Weitz and explores the concept of artificial intelligence in a cautionary tale. To shoot the movie, Edwards and a condensed crew traveled to various locations around the world, blending in the AI world during the editing process instead of relying on green screens.

If there’s one thing director Gareth Edwards’ experience with independent filmmaking taught him, it’s how to utilize your available resources efficiently. From his 2010 indie hit, Monsters, to gargantuan blockbusters like Godzilla and Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, Edwards put that knowledge to the test on The Creator, starring John David Washington, with a radical new way to turn the craft on its head after realizing that “in over a century, we’ve not changed a thing.”

Edwards co-wrote The Creator with screenwriter Chris Weitz (Rogue One), which is a cautionary tale of sorts about the ever-looming presence of artificial intelligence. In this future, humans and AI are warring over control, but that war may soon be coming to an end when the designer of this advanced AI, known only as the Creator, develops a weapon powerful enough to put an end to the war. While grieving the disappearance of his wife, played by Gemma Chan, ex-special forces agent Joshua is assigned to take down this Creator’s plan, but discovers this all-powerful AI weapon is in the form of a child (Madeleine Yuna Voyles). The Creator also features Allison Janney, Ken Watanabe, Amar Chadha-Patel, and Ralph Ineson.

In an interview with Collider’s Steve Weintraub, Edwards gives us a peek behind the curtain to find out how he managed to direct an expansive sci-fi adventure like The Creator on less than the typical Hollywood dime. To create a futuristic, dystopian world, Edwards and a condensed crew traveled to breathtaking locations like “Tokyo, Nepal, Cambodia, Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia” and more to capture scenes with real out-of-this-world imagery. The trick was taking mountainous backdrops and gleaming ocean shots and including the AI-riddled world of The Creator in the edit rather than putting his cast against a green screen. Edwards discusses working with Dune’s talented editor, when he first considered filming this way, and why the assembly cut was nearly five hours long. He also shares fond memories of Collider’s Directors on Directing panel at this year’s Comic-Con. You can check out all of this and more in the video above or in the full transcript below.

COLLIDER: It’s been a few months, did you have fun at Comic-Con with me, or was it a bad experience?

GARETH EDWARDS: Do you want to know the truth?

I do want to know the truth.

EDWARDS: So the way Comic-Con works, as you well know, is you go down some escalators to get to Hall H and you’re also kept away from the audience the whole time you’re backstage, and so the last chance to go to the restroom is like a real maze. I don’t know why I did it, but someone gave me a big bottle of water, and I drank the whole bowl. I don’t know if it was nerves or something, but I drank the entire bottle, and I suddenly went on stage, and I thought, “I’ll just go to pee just before we go on,” and then we go to go on, and there’s no restroom anywhere, and it’s like, “3…2…1…Gareth Edwards, go,” you know what I mean? And I sat there—I’m not joking, I’m really not joking—I sat there, and I was like, “I’m gonna pee myself.” And we were there for, was it an hour and a half?

Yeah, it was 90 minutes.

EDWARDS: And I was like, “I can’t do this. I can’t stay up here.” At one point, I actually looked to see what the audience could see of my trousers [laughs], and you had a barrier thing up because I was like, “I think I’m just gonna pee myself.” I wanted to know how, like, career-ending it would be if I did.

I do remember backstage, you saying to me, “I need to use the bathroom,” and I was explaining to you that you need to go all the way into the convention thing or back upstairs. I didn’t realize the severity of it. The highlight of everything, though, was we went to play your footage from The Creator, the sizzle, and all of you guys went to use the bathroom. I’ve never seen a whole panel go to the bathroom. Louis [Leterrier] sat in the front row to watch the footage, but I was on stage alone.

EDWARDS: I was gonna go when Justin [Simien’s] clip played of Haunted Mansion and I really wanted to pee then and I was like, “It’s gonna look so rude if this clip plays and I just run off stage.” And so I had to just take it, and then my clip came up, and I was like, “I can go now.” But the thing is, you dream of having a clip in Hall H, right? That’s like your dream. And I was just at a urinal hearing it echo through the urinals as some guy was waiting with a Rogue One poster awkwardly for me to sign after I finished peeing. And I was like, “This is this so typical of filmmaking,” you know, “this is how it all plays out.”

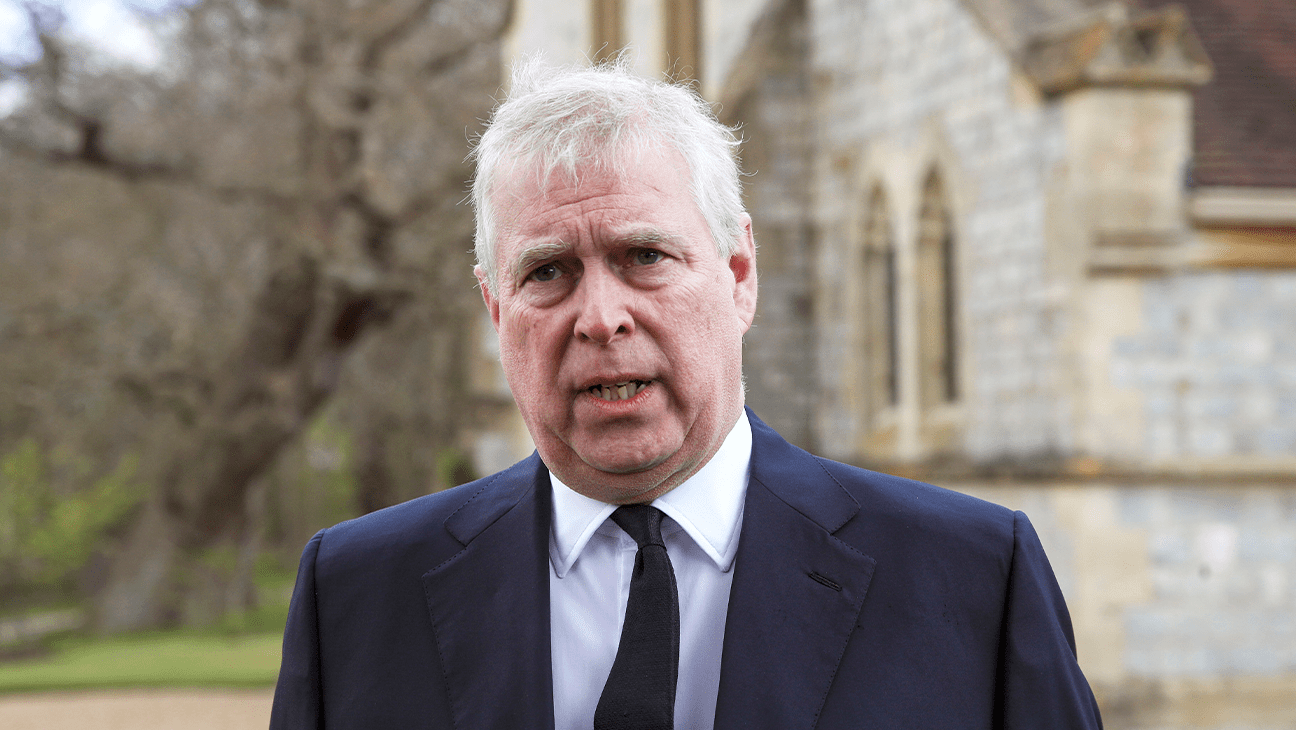

Image via Lucasfilm

Everyone knew you were going to the bathroom…I think. First of all, thank you for sharing the story, but one of the things that’s amazing about this movie is the fact that you basically radically changed how movies can be made and what might happen in the future with the way you shot this and the fact that you didn’t design certain things before you went to location. Can you talk about that?

EDWARDS: What normally happens is, you have this fantasy about a movie you want to make, and you have all these designers and concept artists, and you kind of figure out the world, and it looks great and everything, and then you go, “Okay, how are we gonna do this?” And everyone’s chasing that image. “If you want this sort of shape, you have to build that,” and, “If you want this sort of environment, we can’t do this. We’ll do that against green screen…” And it all sort of becomes like a $200 million movie and never feels as good. So it was like, “Look, let’s do this the other way around,” right? Let’s go make the film. Let’s go to wherever in the world is the best location possible. If you have a crew small enough, then the cost of flying anywhere in the world with that group of people is cheaper than building a set. The second it’s a bigger crew, now it’s more expensive, and so let’s just build a set, right? So it was like, “Get that down so we can go anywhere,” and then it’s like, “Let’s shoot the movie, let’s edit it. Then, when we know what’s in the film, let’s give those frames to our designer, James Clyne, and his team, and they can paint in the science fiction of exactly what’s in the movie.” So, it’s a way more efficient thing. It also meant you can blend in whatever happy accident you had in the real world or crazy location you found just randomly. You can then base your designs on what the foreground looks like and what the mid-ground looks like. So it’s way better all around, and I wouldn’t go back, personally, to the other way.

I was going to say, is this a permanent change to the way you’re going to make movies going forward?

EDWARDS: Yeah. I mean, I think you could push it even further, definitely. I wouldn’t go back to the other way of making it.

Image via 20th Century Studios

It’s crazy that the technology has reached this point where you can do this because, in the past, I guess I was under the assumption that with VFX, you couldn’t do it.

EDWARDS: Yeah, and I think that is the assumption even with VFX people. So what happened was we talked about this process with Industrial Light & Magic, and obviously, everyone’s nodding but thinking, “Oh my god, what are we getting ourselves into?” And so we did a little test, and we didn’t tell the studio, but they gave us some money to go on a location scout, so we went to Tokyo, Nepal, Cambodia, Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia, and we shot…

That’s crazy.

EDWARDS: I know. We just wanted a holiday, right? And I took a camera with me that had a 1970s anamorphic lens and shot a little teaser, short, nonsense thing, and then essentially basically tried to sort of prove this theory and do exactly what we do in the movie and give it to ILM. We didn’t have any tracking markers or dots or any data or any silver balls and all those things you see, we just [gave] it to them. All they had was the footage, and we went, “Can you figure this out?”

They went away, and I wouldn’t say it’s magic because I met some of them recently—I think one of the guys was called Tim, I said I would give him a shout out—but through a lot of blood, sweat, and tears, they managed to track all that stuff back into the computer and pulled it off. I think they were even surprised. So we were like, “Can we do the movie like this then?” And they were like, “Yeah, actually, that was pretty…” Stuff that would normally take, like, a month to do, we were doing in a couple of days or so. In terms of building cities, we didn’t build the cities, we just projected them back onto footage and all this sort of stuff. We showed that to the studio, and for the money we had done it for, they were like, “Oh, if you can make a movie like that, we’re in,” and so we got green-lit basically.

Are you ready for the lessons you’re going to be giving at the DGA to other directors on how you pulled this off?

EDWARDS: No. [Laughs] They don’t want to hear from me.

Image via 20th Century Studios

I have a feeling that there’s going to be a lot of people that want to learn because it’s a lot cheaper to do it the way you did it than the other way. It’s radical.

EDWARDS: You know what was funny, though? When I was prepping the film, or not even prepping it, I was just kind of curious about certain technology, and I went to a studio in LA that does the whole virtual volume stuff. Just as I was waiting, there was a poster on the wall, and it was basically the process of making a film. It was like a diagram of “This is how a movie is made…You write the script, it does this, and these are all the different people…” and I was looking at the poster going, “Okay, why have they got this poster on the wall? It’s so obvious this is filmmaking. What’s this about?” And the guy came up to me and went, “Oh, I see you’re looking at the poster,” and I was like, “Yeah,” and he goes, “That’s over 100 years old.” I was like, “What?” And then you realize in over a century, we’ve not changed a thing. Do you know what I mean? The idea that something so technological, so digital now is a 100-year-old process. There’s got to be an easier way, a better way of doing this stuff, but it’s like it’s some factory, and it just doesn’t want to change, you know what I mean?

Let me switch to something completely different. Hank Corwin is your editor; talk a little bit about working with him because this is a radically different way of making a movie. Did you have a longer cut? How did it work with the editing when you’re doing VFX?

EDWARDS: So Joe Walker did the assembly, who edited Dune and such amazing films, and Hank and Scott Morris basically were the two editors on the movie. Prior to the making of this movie, if you had said to me, “Gareth, what are the two best-edited films in the history of cinema?” I would have gone, “I can’t answer that question because I’m torn between JFK and The Tree of Life.” And they have an editor in common, which is Hank Corwin, and he’s just kind of a bit of a genius. So we essentially ended up in this situation where Hank, he had done big movies, but he hadn’t done [any] with as many VFX shots as we had in this. But it didn’t matter because all we did is we basically cut the movie– One of the things they didn’t have to worry about is there was always something there representing what was going to be VFX. I think it would have been a nightmare if we’d shot one of these films where it was green screen or blue screen, but because we really were in the jungles and the Himalayas, even if there wasn’t the sci-fi temple, there was a temple, and so you could just cut this like a contemporary film.

What they were so good at, Hank, what I love about him, is he does many, many things, but he’s very left field with his thinking. I’m usually the person with a rope trying to drag everyone else off a cliff, and everyone else is going, “No, Gareth, no!” And I’m like, “Come on, let’s get to the edge,” and they’re like, “We’re gonna die!” Hank lives, he’s got a house at the bottom of the canyon, like, he’s off the cliff, right? He’s pulling me, and I’m going, “No, Hank, no!” [Laughs] So it’s really refreshing to be in a situation where someone is challenging you creatively and making you way out of your comfort zone, so that was beautiful.

Then there were only a few times, I remember quite a few conversations, but it wasn’t difficult. I would go away and make selects because obviously, it’s like, “Okay, is one of these jet copter things coming in from the left or the right or forward?” And I’d be like, “I don’t know, I just grabbed a load of footage. Let’s figure it out.” So I would sit and try and figure out what I wanted to happen and maybe drag some silly little font across the screen to represent where some CG vehicle might be, and then we would sit and watch like eight or nine selects and talk about them. You always want feedback. You always want someone to agree with you, you know what I mean? And so we had this really nice relationship between the three of us where we pushed each other but kept other in check. To them, I would think they would say that it was like doing a normal film in terms of the way they cut it, but I know they really enjoyed sitting in on the VFX conversation. So when we talked to ILM, and we did all those Zooms and stuff, they would be listening in because they just were curious about how it all works. But you didn’t need to have a PhD in visual effects to cut this movie because it was all there. We didn’t do green screen and things like that, so it was all quite straightforward.

Image via 20th Century Studios

I like asking this of every director, did you have a much longer cut? Did you have a cut that you were like, “It’s two and a half hours, I don’t know how it’s getting down?”

EDWARDS: Yeah. The first cut was just under five hours. [Laughs]

Wait, what?

EDWARDS: The assembly.

I don’t generally hear assembly cuts being five hours.

EDWARDS: It was under five hours. So Joe Walker and Job [ter Burg] had done this cut of the movie whilst I was shooting, and then Joe went to do Dune 2. So I went around Hank’s house, and he basically hit play on this just-under-five-hour cut. I always expect when I watch an assembly to want to kill myself, you know what I mean? Because basically, you see all the things you did wrong, you see what’s not working. It’s the worst version of the film ever is the assembly. That’s just the way it works, right? But they did this amazing feat of putting everything together really well. But that implies there’s this version of the film with all this stuff in it that you could sit and watch, and I think that’s just not true.

I always wanted to make a two-hour movie. Star Wars is pretty much that and it, pacing-wise, is like spot on. So I didn’t want to outstay my welcome and do a long film. There’s a film critic in the UK who said Stanley Kubrick managed to tell a story from the dawn of mankind until we evolve into being a god in two hours, and 10 minutes, so if you take longer telling your story, you’re just not trying hard enough. I’ve always took that to heart; it feels like they kind of got a point. So it was really a game of Jenga, like, “What can we remove from the film and it not fall to pieces?” It was just trial and error basically until the clock ran out, and we got there, I hope. But it’s a fascinating experience because you show people the movie, and we had a two-hour and 15 version of the movie which we already loved, and we played it to a bunch of people. Everyone disagreed about what they thought was right and wrong, and then the people who ran the test screening said when that happens, it tends to mean it’s too long. So we cut 15 minutes out and got it down to two hours, played it again, and it did way, way better and there were no more disagreements. It was a strange lesson in, “How can you take things out we love and then it be better?” It didn’t make sense, but apparently that’s what happens.

I have so many follow-ups, but I have to go. I’m just gonna say I hope on the eventual Blu-ray you include a bunch of deleted scenes because I would love to see more in this world.

EDWARDS: Okay, point taken. We’ll see what happens.

The Creator is in theaters and IMAX beginning September 29.

Publisher: Source link

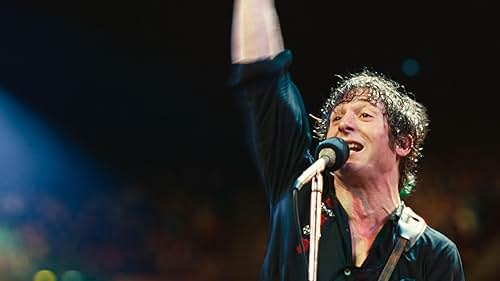

Springsteen: Deliver Me from Nowhere Review

There’s a point in Springsteen: Deliver Me from Nowhere where Bruce’s manager, Jon Landau (Jeremy Strong), plays the tape for his latest record, Nebraska. The Columbia Records executive (David Krumholtz) doesn’t understand what Springsteen is going for. It’s a more…

Nov 3, 2025

Angela Bassett Proves She’s the GOAT in the Best Athena Episode To Date

One of my very favorite things that 9-1-1 does is when the show has "begins" episodes that show flashbacks from the main characters' lives to show impactful moments in their careers as first responders. These episodes are typically about them…

Nov 3, 2025

The franchise’s funniest film to date

One of the reasons for the surprising longevity of the SpongeBob SquarePants franchise is in its main character’s very sponginess. Along with most other characters that reside in Bikini Bottom, SpongeBob (Tom Kenny) is stretched and molded, cut up, sliced,…

Nov 1, 2025

A Storm at Sea Without Depth

Simon Stone’s The Woman in Cabin 10 sails into familiar waters of psychological paranoia and maritime mystery, but it never quite finds its sea legs. Adapted from Ruth Ware’s 2016 bestselling novel, the film attempts to be both a sleek,…

Nov 1, 2025