Martin Scorsese on Representing the Osage in ‘Killers of the Flower Moon’

Oct 22, 2023

The Big Picture

Martin Scorsese aimed to accurately represent the Osage Nation while telling the story by incorporating cultural elements and rituals. The filmmakers worked closely with Osage experts to ensure accuracy in the portrayal of Osage traditions and customs. Lily Gladstone’s performance in the film is highly impressive, showcasing her intelligence, emotion, and activism in a nuanced way.

From Academy Award winning director Martin Scorsese and screenwriter Eric Roth, and based on the bestselling book by David Grann, the western crime drama Killers of the Flower Moon explores the 1920s murders of members of the Osage Nation and the mysterious circumstances surrounding them. At the center of it all is the relationship between Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio) and Mollie Kyle (Lily Gladstone), a woman with ties to her family’s riches and a personal connection to some of the victims.

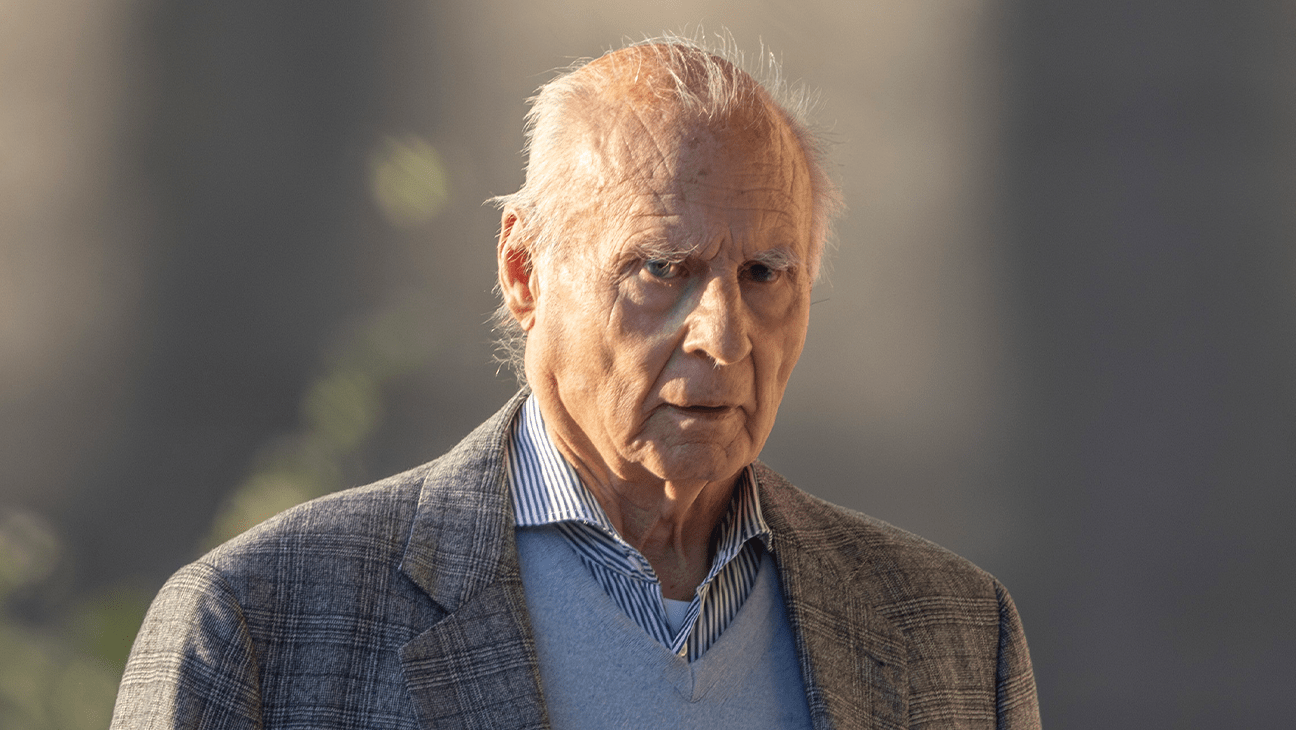

During a press conference to discuss the new film, out in theaters and soon to be available to stream at Apple TV+, Scorsese talked about the steps they took to accurately represent the Osage Nation, why they chose to focus the story where they did, his experience in Oklahoma, telling a historically accurate story that’s emotionally resonant, Gladstone’s involvement with the portrayal of her character, his longtime collaborative relationships with DiCaprio and Robert De Niro, and being driven by the pace of the music.

Question: What steps did you and the production team take to ensure that the Osage community feels accurately represented?

MARTIN SCORSESE: I had an experience in the seventies where I began to become aware of the nature of what the situation was and still is. I had been unaware of that because I was too young. I was in my twenties, and I just didn’t know. It’s taken me years. I’m fascinated by, how do you really deal with that culture in a way that is respectful, and also isn’t hagiographic and doesn’t fall into the noble native and that sort of thing. How truthful can we be and still have authenticity and respect and dignity, and deal with the truth honestly, as best we can? Having said that, that story, when I read it, indicated to me that this would probably be the one that we could deal with that way, particularly by getting involved with the culture of the Osage and actually placing cultural elements, rituals and spiritual moments. People use that phrase “mystical realism.” This is real. The dream is real. The ancestors come. The owl is real, in a sense. And so, for me, I wanted to play with that world, in contrast with the white European world, and I felt that this afforded us the possibility.

The David Grann book is excellent, but it also has the subtitle, The Birth of the FBI. For about a year and a half to two years, I was doing The Irishman and (co-writer) Eric Roth and I were working, and we felt that we took the story of the birth of the FBI as far as we could take it. I wanted to keep balancing with the Osage, and it was getting bigger and bigger, and more diffused. Ultimately, this was supplemented by the times that we went out to Oklahoma and met with the Osage. My first meeting was with Chief Standing Bear and his group, and it was very different than what I expected. They were naturally cautious. I had to explain to them that I was going to try to deal with them as honestly and truthfully as possible. We weren’t going to fall into the trap of the cliché of victims or the drunken Indian, or any of that sort of thing, and yet tell the story as straight as possible.

What I didn’t really understand the first couple of meetings was that this is an ongoing situation out in Oklahoma. In other words, these are things that really weren’t talked about in the generation I was talking to and the generation before them. It was the generation before them that this happened to. They didn’t talk about it much, and the descendants are still there. And so, what I learned from meeting with them and having dinners with them, was that a lot of the European Americans there were good friends. What is that about us, as human beings, that allows for us to be so compartmentalized? One has to remember that Ernest loved Mollie, and Mollie loved Ernest. It’s a love story. And so, ultimately, what happened was that the script shifted that way. That’s when Leo decided to play Ernest instead of Tom White. By that point, we started reworking the script and instead of from the outside in, coming in and finding out whodunit, in reality, it’s who didn’t do it. It’s a story of complicity. It’s a story of sin by omission and silent complicity, in certain cases. That’s what afforded us the opportunity to open the picture up and start from the inside out.

Image via Apple Studios

The film takes place in Oklahoma, and you were adamant about shooting the movie there. When was the first time you visited Oklahoma and what was your impression? How did you begin to visualize the film taking place there?

SCORSESE: The first time was in 2019, I think. It’s a little confusing because of shooting The Irishman, doing the CGI on The Irishman, which was a longer post-production of four or five months, and then COVID hitting. But I know we were there before COVID. We had at least two trips there before COVID. For me, I am a New Yorker. I grew up on the Lower East Side of New York. I’m very urban. I don’t understand weather that much, or where the sun is when you’re on the set. I was very surprised to learn that it sets in the west. I was driving down Sunset Blvd. one time, about 30 years ago, and I saw the sun setting and said, “That’s great. It’s Sunset Blvd. The sun sets in the west. Oh, I get it.” So, when I got there, all I can tell you is that those prairies are quite something. They open your mind and your heart. They are just beautiful, especially driving on these straight roads through a prairie on both sides, with wild horses and bison and cows. The wild horses are just out to pasture for the rest of their lives, and it was idyllic. I said, “Where do I put the camera? How much of the sky? How much of the prairie? Should it be 185, or should it be 235? We’ve gotta go 235. You want to see more of this land.”

And then, I began to realize that the land itself could be sinister. In other words, you’re in a place like this and you don’t see people for miles. You could do anything, particularly a hundred years ago. I realized this is a place where you don’t need the law. They have the law, but the law isn’t working that way. You can make the law work for you, if you’re smart enough, as we know now, because many people do. What I mean by that is that it’s still wide open territory. The place, as beautiful as it is, can shift to being very sinister, and what I wanted to capture, ultimately, was the very nature of the virus of the cancer that creates this sense of an easygoing genocide. That’s why we went with the story of Mollie and Ernest. That’s the basis of the love, and the love is the basis of trust, so when there’s betrayal that way and that deep, and we know for a fact that it was that way, that’s our story.

How did you approach telling a historically accurate story that’s emotionally resonant?

SCORSESE: We had a lot of support from the Osage experts, who were giving us the indication of how to go about these things. We tested the accuracy of the rituals, the baby naming, the wedding, the funerals, everything that happened at the funerals, and all of that sort of thing. In some cases, there is wiggle room because, quite honestly, the last two generations of Osage forgot about or were taken out of their experience because they had to become like White Europeans, or Christians or Catholics, or whatever. In fact, there’s a new resurgence of learning the language. We had language teachers there. Lily Gladstone learned the language, so did Leo, and so did De Niro, who really fell in love with it and wanted to do more scenes in Osage. They were all learning to put their culture back together through this movie, and we were going with them. Sometimes they would say, “You have a little room here to play with it and have some creative license.” That’s the way we did it, throughout every scene. That was done through pre-production and during the shoot.

Image via Apple Studios

People are going to be really impressed with Lily Gladstone’s performance. What was the first scene that you shot with her?

SCORSESE: I saw her in Certain Women, Kelly Reichardt’s film and I thought she was terrific. And then, COVID hit and we weren’t able to meet. After the pandemic was calming down, we met on Zoom and I was very, very impressed by her presence. The intelligence and emotion that’s there in her face, you see it, and feel it. It’s all working behind the eyes. You can see it happening. Also, there’s her activism, which wasn’t overtaking the art. In other words, the art was in the activism. The art takes over in a way that’s more resonant when you see the movie. You may think about it more than a person preaching at you. The first big scene we did was one of my favorite scenes, where she has dinner with Ernest alone and she’s questioning him in a little bit of an interrogation. “What are you doing here? Are you afraid of him? What’s your religion?” And then, you begin to see there, the connection between the two. She knows what she’s getting into. The script was ultimately created by these moments. There’s also the scene where he’s driving her in the taxi, and it’s only one shot. He says something about, “I wanna see who’s gonna be in this horse race,” and she answers in Osage. He goes, “What did you say?,” and she says it in Osage again. He says, “Well, I don’t know what that was, but it must have been Indian for ‘handsome devil.’” That’s an improv. You see her laugh for real. That moment, you have the actual relationship between the two actors. Those were the two moments when we felt very comfortable with her. And also, we had a feeling that we needed her to help us tell the story of the women there. We would always check with her and work with her on the script. There were scenes that were added and scenes that were written, constantly.

You’ve had a 20-year partnership with Leonardo DiCaprio and a 50-year partnership with Robert De Niro. Why have you returned to them both so often over the years?

SCORSESE: In the case of Robert De Niro, we were teenagers together. He’s the only one who really knows where I come from, the people I knew, and that sort of thing. Some of them are still alive, and he knows them. I know his old friends. We had a real testing ground in the seventies, where we tried everything and we found that we trusted each other. It’s all about trust and love. That’s what it is. That’s a big deal because very often, if an actor has a lot of power, and he had a lot of power at that time, an actor could take over your picture. If the studio gets angry with you, the actor can come in and take it over. With him, I never felt that. There was a freedom, there was experimenting, and we weren’t afraid of anything. I wasn’t afraid to do something. I just did it. And years later, he told me he worked with this kid, Leo DiCaprio, in This Boy’s Life. He said, “You should work with this kid sometime,” and it was casual. But a recommendation at that time, in the early nineties, was not casual. He said it casually, but he rarely said that. He rarely gave recommendations. And so, the years went by and I presented Leo with Gangs of New York, so we worked together on that. He made Gangs possible, actually. He loved the pictures I made and he wanted to explore the same territory. We developed more of a relationship when we did The Aviator. Towards the end of it, there was something happening in the maturity with him. I’m not quite sure, but we really clicked in certain scenes, and that led to The Departed, where we became much closer.

That was a project where Bill Monaghan and me were the people who were writing all the time and recreating that character that he played. And so, during that time, we really found out that, even though it was 30 years difference, he has similar sensibilities. He’d come to me and say, “Listen to this record, and it’s Ella Fitzgerald. I grew up with it and he wasn’t bringing me anything new, but he likes it, so that’s interesting. He’ll call me and say, “I had a cold and I was looking at Criterion film. I wanted to catch up with some of these classics and I saw this incredible movie. It’s a Japanese picture, called Tokyo Story. Did you ever see it?” I said, “Yeah.” It took me a few years to catch up. I couldn’t even understand the Ozu style, seeing it the first time in the early seventies because I was used to Orsen Welles. But this guy got it from watching it on a big screen TV, and that’s very interesting to me, to be open that way, to other parts of our culture, and the curiosity that he has about other people and other cultures.

There’s a trust. Even if we can’t get it right away, we know we’ll come up with something. Maybe other people have relationships where they come up with it faster, but we don’t. We just work it through. For example, the scene between Leo and Bob in the jail at the end, ultimately was finally written a few days before we shot it. We had said so much and it could have gone so many different ways. It was about, what does the picture really need? How much more is there for them to say to each other, after all that’s happened? And so, we went that way. It’s trust, particularly doing The Wolf of Wall Street, by the way. He came up with wonderful stuff that was outrageous. I pushed him, he pushed me, and then I pushed him more than he pushed me, and suddenly everything was wild. It was really quite something. And he had good energy on the set. That was also very important. In the mornings, I’m not really good. I’d get on set, and then I’d see him or Jonah Hill or Margot Robbie, or him or Lily, and suddenly they were like, “Hey! Okay, let’s work.”

Image via Apple Studios

Your films have a musicality, in your framing, camera movement, sound, silences, and where you choose to cut a shot. What informed the rhythm of this and what music were you hearing?

SCORSESE: The way I like to make pictures, for the most part, is like the pacing of music. It’s the boxing scenes in Raging Bull, or the ballet scene in The Red Shoes, where everything is seen and felt from inside the ring, inside the fighter’s head, or everything is felt and seen inside the dancer’s head. Sometimes I play the music back on the set. In the case of Goodfellas, that happened a number of times. The end of “Layla,” for example, was played back as we were doing the camera moves. For me, ultimately, I’m trying to get to the movie being like a piece of music. That’s why I do music and films, at the same time. I’m trying to get to the pacing and rhythm of something that can be played. If a film is playing on TCM, I turn the sound off and it’s living with me while I live with it. Whether it’s a Hitchcock or a Ford, I’m looking and I can tell there’s a musical rhythm to the pacing of the camera, the size of the people in the frame, the editing, and the camera movement. I can feel it. That’s how I exist, in a sense.

For me, it’s really about getting the pace of music. That’s done very carefully on set, but also even more carefully in the editing. That’s why this picture is more like a bolero, where it starts slower, and it moves slowly and in circles, and then suddenly gets more intense, and it goes more and more until it explodes. I felt it. I couldn’t verbalize it the way I am now, but I felt it in the shoot and in the edit. The music that kept pushing me was what Robbie Robertson had put together, particularly that bass note that he was playing when Ernest drops her off, for the first time, at Mollie’s house. She looks at him and turns and, all of a sudden, you hear it. I said I wanted something dangerous and fleshy and sexy, but dangerous, and that beat took us all the way through. The drive of the movie is what Robbie put down, and we pulled it through that way.

Killers of the Flower Moon is now playing in theaters.

Publisher: Source link

’28 Years Later,’ ‘F1,’ ‘The Materialists,’ ‘Ballerina’ & More

While June TV is on the quieter side, the film slate is picking up with some major releases heading for theaters. From the latest in the “John Wick” universe to a new original Pixar film and Brad Pitt teaming up…

Jun 5, 2025

Denis Villeneuve Claimed This Underrated 2000s Benicio del Toro Drama Is One of The Greatest War Movies Ever Made

Even the most expansive biopics can only hope to cover a portion of their subjects' lives, as the journey from birth to death could never fit into two hours. That's perhaps why Steven Soderbergh decided to divide his Che Guevara…

Jun 5, 2025

Brad Pitt’s Divisive Horror Movie ‘World War Z’ Sprints Onto Streaming

While the peak of the zombie genre may have come and gone, with the upcoming release of Danny Boyle's 28 Years Later, fans are diving back into some of the best and most divisive zombie movies. As well as classics…

Jun 5, 2025

Greta Gerwig’s Titular Indie Emphasizes the Importance of This Lesser-Known Genre

It's a miracle that Greta Gerwig emerged as one of our most exciting filmmakers working today, considering that her roots began in the much-maligned subgenre of mumblecore. Peaking in the 2000s, mumblecore is a style of indie, microbudget light dramedies…

Jun 4, 2025