Steven Soderbergh on Full Circle & How William Friedkin’s Work Influenced Him

Jul 30, 2023

The Big Picture

Full Circle is a melodramatic crime drama series with interconnected storylines and hidden secrets, taking viewers on unexpected twists and turns. Steven Soderbergh collaborated with writer Ed Solomon, whom he found to be more complex and soulful than his comedy-focused resume suggests. The editing process for Full Circle was dynamic and constantly changing, with regular feedback and adjustments based on the evolving narrative.

[Editor’s note: The following contains spoilers for Full Circle.]From director Steven Soderbergh and writer Ed Solomon, the six-episode Max series Full Circle follows an investigation into a botched kidnapping, the individuals connected to it, and the secrets that have long been hidden. As the puzzle pieces come together, revelations make the three seemingly unrelated storylines take shape as a more intertwined crime drama that runs as deep as the ties that bind family.

During an hour-long roundtable with a small handful of outlets including Collider, Soderbergh discussed all aspects of Full Circle, as well as his own filmmaking process. He talked about why he found the initial idea so intriguing, collaborating with Solomon, how editing while he was shooting helped to inform the finished series, the influences on this project, weaving in the Guyanese story and characters, why they didn’t use flashbacks, the final scene between Claire Danes and Zazie Beetz, and how he feels about A.I. as a storytelling tool.

Question: You’ve mentioned that Ed Solomon brought the idea for Full Circle to you, before he actually wrote the script. What did you find so intriguing about the initial idea and how did that intensify, once you read the complete script?

STEVEN SODERBERGH: It felt like a really interesting combination. I viewed it as a melodrama. I viewed this whole thing as a real New York City melodrama, and I liked the sprawling aspect of it. You think it’s about this group of well-off white people being victimized, and then, over the course of the show, the whole thing starts to tilt, and by the end of it, we’re in a very different place than where we started. I liked the bait and switch aspect of it. So, it was a melodrama that had this very interesting subterranean thematic thread that’s bubbling along, that eventually comes up and takes primacy in the last two episodes. All of that just appealed to me. It seemed like the best of both worlds, of just operating, on a superficial level, as a melodrama, and yet there was enough of the actual world in it to prevent it from being single-use plastic.

Image via Max

What was it like to collaborate with Ed Solomon and blend together your different tastes?

SODERBERGH: It came about in a very serendipitous way. Ed and I met and started to know each other about 20 years ago. We had mutual friends, and we just started meeting up occasionally and talking. And then, I ran into him in Canada when he was shooting a movie he directed, called Levity, many years ago and, and started having more serious conversations about filmmaking. My sense was that the superficial read on Ed and Ed’s capabilities was not entirely accurate, based on the conversations that we were having. This was a much more soulful and serious person than his resume might suggest. He’s obviously also very funny. I’m just saying that, if you looked at his IMDb page, at the point where he and I started hanging out, he’s the joke meister, but that was only part of the picture that is really Ed. This was in 2014, when I was working on developing this branching narrative app and was in the midst of writing a demo that I was gonna shoot, to show how this app would work. I was trying to find somebody that I thought would rock what I was trying to do, and I wanted it to be fun, but I also wanted it to have some kind of drama. Casey Silver was involved in this, and out of the blue, I said, “Why don’t we get Ed to help us write the demo for this branching narrative thing?” And he said, “I love it. Let’s do that.” So, Ed came on and helped finish the script for this demo, which was then bought by HBO and turned into Mosaic. That was how we really started our collaboration.

As we were doing the demo, I said, “Okay, they’ve bought the concept, so now we’ve gotta write a show. Do you wanna write the show?” He said, “Sure.” So, we started working on Mosaic. And as often happens, when you spend a lot of time standing next to somebody, ideas come about and you start to pitch things. And so, while we were at the tail end of Mosaic, we started talking about two things. We started talking about No Sudden Move, and Ed started talking to me about what would become Full Circle, which is a fusion of a story that he read in the newspaper, in the early 2000s, about an insurance scam criminal ring in Queens, where they were taking out policies on transient people, paying the premiums, and then getting rid of them. That was in 2002 or 2003. And then, it was a variation on the premise of High and Low, the [Akira] Kurosawa film. You won’t spoil this for people, but what Ed pitched to me was, “What if it’s High and Low, but both of the kids are his, and nobody knows that?” I said, “Oh, that’s interesting.” That’s how things began.

We did No Sudden Move first, but while he was doing that, he was writing Full Circle. It was supposed to originally include a branching narrative app version, but last spring in London, when I was shooting Magic Mike’s Last Dance, I said to Ed, “Look, I can’t do both of these, at the same time.” On Mosaic, we were able to do that because I was repurposing the footage to use in both ways. I was using the same footage for the linear version that I was using for the app. That’s why that was not a problem. My vision for the app version of Full Circle was completely different imagery with a completely different approach, directorially, with different cameras and different everything. We had the Full Circle script, which was 400 pages that we’re shooting in 65 days. Then, we would have the app version, which was 170 pages, in which there’s no overlap. It was new stuff. And I told him, “I can’t do it. I can shoot fast, but I cannot shoot that fast.” So, we had to throw all of that away. Some of that 170 pages leaked its way back into the linear version. It’s not like we just never looked at it again. I wasn’t looking forward to that lunch, where I was gonna sit down and tell him, “Yeah, all that work you did, I’m throwing that out.” But he understood, and as we got further into it, he acknowledged that we were having a hard enough time just wrapping our minds around this normal version, forget about a branching narrative app.

From the outside, it all looks very structured and inevitable, the way these things develop, but the reality is that there are so many variables and you never know which thing that you’re trying to get going is gonna be ready. Ed and I were batting six episodes back and forth for a couple months, felt good about it, turned it into Max and they greenlit it immediately, and then there was a moment of, “Oh, shit!” We thought there would be more back and forth, or more of a development process, but suddenly, it was like, “Okay, great, when are you starting? How much is it gonna cost?” We really had to shift gears and attack it more quickly than we anticipated. We thought that, once we turned it in, there would be a fairly significant amount of time before it was actually gonna shoot, but it turned out that they wanted to go, and they wanted to go immediately.

Image via Max

While you were shooting this, you were also editing it. How much did that change things, as you were seeing it laid out and you could see what was working best? How did that change, expand, or even pull back on what you were doing, and was there anything that most dramatically changed, as a result of that?

SODERBERGH: It was changing constantly. Probably more than anything that I’ve worked on. There were layers of feedback. After we wrap, within an hour, or an hour and a half, I have the footage, I start to cut, and I post. If it was a day shoot, I post all the material the night that we shot and edited. If it was a night shoot, it’s probably the next afternoon. And then, very quickly, the brain trust and the studio are seeing cut footage of what was just shot, and it’s got sound effects and music on it. It’s a pretty fair approximation of what we’re trying to do, so that there’s that initial feedback. Does that scene work? Are those scenes working, generally, out of context? Then, every 10 days to two weeks, I start posting what I have of each episode, in the episode form, so you can start to see, slowly, the larger picture of the show filling out, and that creates another layer of feedback about starting to see transitions now and longer runs of scenes, and it’s starting to emerge. This is where you start to have conversations about, how’s it feeling? How is it working? And invariably, you start to see things that you want to change, either in what you’ve already shot or based on what you’re looking at. You go, “Hey, maybe we need to not hit that thing so hard because it really imprinted well on this scene.” You talk about what we’re trying to keep afloat, or whether it was a little too subtle, so that when we get to this other scene with the family again, we’ve got to hit this other notion a little harder. You’re starting to have those conversations, which get more significant, the further into the shoot you are.

In one specific case, we had a big scene coming up, in the sense that it was a big scene within the narrative, but also a big scene for me, in terms of staging and how I wanted to do it, and what I determined was that I was bumping on this scene. So, I went to (screenwriter) Ed [Solomon] and I said, “Hey, we’ve got a scene coming up in a week that I’m really struggling with, and I think we should take a different approach, knowing that if we do take a different approach, we’ve not only got to rewrite the scene that I’m talking about, but we’re gonna have to rewrite all the scenes that follow it and that have the main character in that scene in it, and we will have to go back and reshoot two scenes prior to that big scene, that we’ve already shot, to tee up the new approach that I wanna take.” Fortunately, Ed said, “I agree,” and we started working on it, right that moment. So, by the time we got to the following week, we had rewritten the scene that we were gonna shoot, we had plugged into the schedule both the scenes that needed to be reshot, that we’d already shot, and the new scenes that were gonna follow the new approach, and we just integrated it into the overall schedule. That’s not unusual, but if you don’t have people who are fluid in their thinking, it can create panic. That was just part of the process, throughout.

And then, when we had the whole show assembled and the brain trust was looking at it, the studio was looking at it, and our family and friends group, which is about 20 or 25 people, were looking at it. That’s when the most significant changes began. We did a lot of work within the six weeks after the first cut to reshape the show, rebalance the show, pull out some strands of narrative, and expand other strands. It all had to be done really quickly because the cast was already getting ready to go off on to other projects, all over the world, so there was a very intense period, right after the first of the year, of re-cutting and reshooting. To give credit to the Max crew, they had to adapt to our rhythm. I was very sensitive to the fact that they’ve got 25 shows that they’re doing this on, and we only have one. So, they’d send me a round of notes, I would respond to the notes, send them a new cut of the whole show within a day, and they would have to watch the whole show again, and they did that. We did that multiple times, until it was finished. They worked really hard and really quickly to get this all to where we ended up.

Every year, there’s a list of the films and TV shows that you’ve watched. In 2022, you watched [William] Friedkin’s Sorcerer three times, when this would have been in production. Was that on your mind while making this, and were there other films that you were thinking about, as well?

SODERBERGH: Yeah, I was thinking about Friedkin’s work of the seventies a lot. I was also thinking about Sidney Lumet’s New York movies from the seventies a lot. In terms of the filmmaking style, I wanted it to be precise, but I also wanted it to be blunt. I don’t know how else to describe it. That was something that I was surfing, moment to moment. Some scenes, I felt required a little bit of an operatic or baroque approach because we are making a melodrama and I wanted the press and release, visually. You might have a scene where you’re just totally unaware of what I’m doing, as a director, and then in other scenes, for a very specific reason, the filmmaking leans forward a little bit. I knew, from the get-go, that I wanted to employ a very traditional melodramatic score. That was always gonna be part of what we were doing. I wanted the score to not be trendy or hip, or anything like that. I really wanted a classic Hollywood approach to the score, to blend in with this idea that we were making an urban version of Peyton Place. In visual terms, I wanted the texture of something like French Connection or Sorcerer, which are gritty.

Image via Max

You mentioned the bait and switch of how this starts off seeming like it’s about this wealthy white family, but a lot of the narrative, especially in the later episodes, centers around the Guyaense characters, particularly the brother and sister. When you were of involved in the casting process and putting the show together, what were you looking for, when it came to those roles? Did you have any concerns about entrusting so much of the narrative to those younger actors?

SODERBERGH: That’s where having Carmen Cuba is crucial. We, and Ed, especially, spent a lot of time trying to make sure that those characters were given the treatment that all the characters were given. I wanna shoot everybody like they’re movie stars that are the leads of this thing. That’s not just a directorial approach. That has to be reflected in the writing, as well. The whole thing was designed so that Louis and Natalia are the heroes of this. They’re the only people in the entire show who are unsullied by making bad choices. They’ve found themselves in a bad circumstance, but they’re good people and they’ve been trying to do the right thing. They’re the only ones that emerge morally unscathed. Making sure that this process of giving them that kind of primacy is gradual was something we talked about a lot.

We wanted to find people you haven’t seen before. They’re young. You’re looking at people who, unless they started acting when they were children, haven’t done a lot, so it was a fairly intensive search that Carmen did. One of the things that I decided, from the get-go, was that I wasn’t gonna ask where they were based. I didn’t wanna make decisions based whether they lived in New York. So, Carmen sent me a lot of people to look at, and I would start to narrow it down. It’s a mosaic, so I was looking at faces. I was putting them up against people that have already been cast, so I was looking at a gallery. And then, I’d say, “Okay, I think it’s this person, this person, and this person.” And Carmen would go, “Well, Sheyi Cole lives in London, as does Phaldut Sharma. Jharrel [Jerome] lives in Los Angeles.” I said, “We’re just gonna have to figure this out. We’ve gotta have who we’ve gotta have.” Fortunately, we got all of our first choices and figured out, budgetarily, how to make that all work.

As the show was being shot and we were looking at the footage, Ed and I were both always looking for ways to expand the storyline of the kids, particularly Louis and Natalia and Xavier and Garmen. That relationship, in the original script, was the same, up to a point, but then during shooting, we decided to go with something a little bit different. I was enamored with this idea that Garmen views Xavier as a being the only person in that group that really knows what he’s doing and as a potential partner in an escape plan. That was something that was really developed while we were shooting because, in the original script, that idea didn’t exist. That grew out of my response to what I was seeing. As we were watching footage and watching the episodes fill out, I was saying to Ed, “I really like this relationship.” It used to end like in episode four, and I said, “I don’t want it to end. I think we should keep going with this.” And so, we started building out this idea that Garmen sees him as part of his plan to get away from Mrs. Mahabir, who he feels has completely lost touch with reality and can’t be trusted. And so, all of these issues about loyalty were developed while we were shooting.

You have actors in this that you’ve worked with before and actors that you’ve never worked with before, which seems to be what you do on your projects. Are there ever times when you go back to an actor that you’ve previously worked with because you see them in a role that maybe they don’t see themselves in, and that either takes convincing to get them to do it or they just tell you no? Did that happen with this series, at all?

SODERBERGH: This time, no. Certainly, if I’ve worked with somebody multiple times and I’m approaching them again, I’m hoping that it’s something that provides an opportunity to be different than the piece they’ve done before. I got to work with a lot of really terrific new people, who now go onto the list of people I wanna work with again. I hadn’t worked with Dennis [Quaid] in 23 years, so it was good to see Dennis again. Zazie, I just worked with a couple of years ago. Claire Danes, I’ve been a fan of since she started her career. Tim Olyphant, I remember seeing in Go and thinking, “Wow, that guy’s really compelling. I’ve gotta put him on the list.” It’s fun to gradually begin to pull those people in. But at the end of the day, it’s really about trying to create an environment that’s not about me, it’s about the thing that we’re here to do. Phaldut Sharma, who plays Garmen, described it, and not because I asked him – I didn’t ask him, “So what was it like to work with me?” – but he was just talking about it at the wrap party, where he was talking to one of his fellow actors and I happened to walk up with a drink in my hand and he said, “I was just talking about how you were in control of this, but I felt like you weren’t there, at the same time.” When I figure out how we’re gonna start, we just start. They show up on the set and they’re already wired, they’ve been through makeup, and the set is lit. As soon as I feel like the thing has reached a point of being ready, we start shooting it, and we don’t stop until it’s done. So, he said it was this combination of me being there and not there, at the same time. He felt safe and free, which is good because I don’t want him thinking about me. I want him thinking about what he’s doing and what his scene partner is doing. I don’t want him worrying about me and whether I’m gonna be okay. He doesn’t need to check with me like that. That was a perfect example of what I’m looking for, which is a structured discovery process where everybody feels that they’ve got agency. Whether he meant that as a compliment or not, I took it as a compliment.

Image via Max

How did you come to cast Jim Gaffigan in his role? He’s obviously done dramatic work in the past, but were you looking to do something specifically against type?

SODERBERGH: I’ve been a fan of Jim’s for a long time. I’ve had good success, creatively, casting comedians in supporting dramatic roles. So, when Carmen brought his name up, I thought, “As a foil for Zazie [Beetz], you can’t get much better than this. This is gonna be really interesting, to see the two of them going at it.” And he was lovely. He’s very good, and he’s also value added, in the sense that he’s just a really fun presence on set. I didn’t know the man. You never know anybody until they show up on set to go to work, but he’s as you would hope. He’s very funny, he’s very prepared, and he’s very good at his job. The only time that I was concerned was that scene where we meet him for the first time, with Zazie. We shot that scene twice, and both times, the script called for him to eat an entire microwavable burrito and put it into its mouth, just as he’s finishing the last line. I’m not somebody who grinds on a lot of takes, but there were a couple of different sizes and the guy had to eat eight of those things. That was the only time that I was concerned. I asked him, “Is this a problem, Jim? I don’t wanna have this go on for too long, but is this a problem? Can we do one more?” And he was like, “No, these are actually really good.” I don’t know if he’s not allowed to eat those outside of shooting, but he was really wonderful. The only tricky part about working with Jim is that he’s incredibly busy. So, for instance, when I said, “I wanna go back, I think we can do this scene again,” his stand-up schedule is ridiculous. The guy is constantly doing shows, all over the country.

Each side of this story involves characters struggling with their morality in a bunch of different ways. How did you tackle developing these characters and showing all of their struggles with shorter screen time for some of the supporting characters?

SODERBERGH: The two worlds are struggling with morality questions at different time scales and with different levels of proximity. For the Brown family and the Chef Jeff universe of it all, the philosophical question is, if I said to you, “If you press this button, I’m gonna give you a million dollars in cash, but something bad is gonna happen to somebody that you don’t know and that you will never meet, on the other side of the world. Are you ok with that?” That’s the dilemma. It turns out that they said, “Yeah, we’re fine with that,” and they did press that button, 20 years ago. For the other characters, the moral issues are extremely near term and potentially lethal immediately, but their options are extremely limited. Aked’s story, to me, is a tragedy. That’s what I talked to Jharrel about. This is a guy whose ambition doesn’t really match his talent. He wants to be a bigger part of this whole thing, but he’s not really equipped to do it, so he’s trying to leap further than he can jump. He, to me, was fairly clear. He answered the question by saying, “I’m willing to do pretty much anything to get what I want,” although he does draw the line at what they’re gonna do to this kid. He thought, “Okay, we’re gonna hold the kid and get the money, and then we’ll give the kid back.” When it begins to dawn on him that they’re actually gonna kill this kid, he starts to now wonder what he’s into.

But the real heart of the story to me is Louis and Natalia. When you see the two of them, and it happens pretty quickly, Mrs. Mahabir says, “I need two people from Guyana. Go get me two people from Guyana.” We meet them, we see them leave, they’re excited, they show up in New York and in four scenes, they’ve gone from, “This is the best thing that’s ever happened to me to,” to “This is the worst thing that’s ever happened to me.” It’s nine minutes of screen time, from them being on that boat to them sitting in that diner and realizing they’re in hell. That, to me, was heartbreaking, but also really traumatic because you’re wondering, “Now what?” They have no agency, they’re completely stuck, their passports have been taken, and they’re at the mercy of people who view them as disposable. So, what do they do?

Louis and Natalia are the only people that manage to get out of this. Although at the end of it, they’re back to where they started, and I guess they’ve learned something, but it’s not a happy conclusion. It’s good they survived, but that was a very difficult ride, for them to get back to where they started. With the way that information is released, the whole show is engineered to that final shot, where they come through the gate, walk through the field, and you see the complex that’s just rotting and a version of the billboard that’s 20 years old, saying, “Here it comes.” It’s wild. That’s a structure that actually exists. The backstory of how that structure came to be is not what’s in the show. It was weird to be there and look at it and go, “Somebody thought this was gonna be a thing.” When you look at it, it’s very strange. It’s a strange building that’s plopped down in the middle of this lot. From the very beginning of the script, it was all engineered to that one last shot.

Image via Max

So many of the secrets and revelations, particularly with the development in Guyana and the bribery, come out through conversations between the characters. Did you ever consider doing flashbacks to reveal some of that information?

SODERBERGH: Yeah, we did. I think we determined that it was more organic, with the style of the storytelling, to have us learn that as the characters learned it, in this case, mostly with Zazie and a little bit with Claire [Danes]. We really wanted to save those final pieces of the puzzle for that big dialogue scene between Claire and Zazie in the hospital. I’m the first person to tell you, “Let’s figure out a way to show something and not tell it.” When people say, “What’s the biggest difference between movies and television?,” I go, “I can tell you that right now, in a movie, people don’t talk for long periods of time. That’s the difference between movies and television.” However, having said that, I am not afraid of two people in a room. I built my whole career on two people in a room. In this case, I felt it was justified. The audience, six episodes in, is desperate to know what the fuck happened. They want to know what actually happened. And I felt there was something satisfying about knowing because it’s not only important for the audience to finally have it all come into focus, but it’s a critical plot point for Claire to finally have all of this in focus. She’s now gonna turn and make a really big decision about her life.

My attitude about the end of this is that she’s going to jail, and she’s made that choice. She’s the character, out of all the people that we see, that actually has the biggest arc and the biggest shift. In a sense, she has to be convinced, in the same way that the audience is convinced, that there is no way out. Once you understand what happened, you have to accept responsibility. So, I wasn’t scared of that. We shot that scene twice because it was so important to get right, and there were subtle variations in the two, but they were really critical. That was February, and Claire was now four and a half months pregnant instead of two months pregnant, so we had to shoot that a certain way, but it was that important. Nothing is more satisfying to me, in a weird way, of distilling it into something that simple and shooting it. It was two angles being shot, at the same time, with Claire and Zazie. That was it. I stripped everything away except their faces and what they were saying. I think that can work, as long as you’re not doing that all the time. The reason that scene lands the way it lands is because it’s not like actually any of the other scenes that we shot, in terms of the length of it and the simplicity of those two closeups. Those are the two biggest closeups in the entire show. You’re working toward this moment of the two of them, sitting a foot and a half apart.

There was so much trial and error, trying to figure out what information to give and when, and who was transmitting it. It was such a clinic in the difference between reading a script and seeing something. I’m so frustrated by the script format because it’s such a non thing. The biggest lesson we learned was, in the script, the cross-cutting between all the stories was a lot more aggressive and it read great. When you read it, you felt like you were really moving everywhere, but when you watched it, you realized that you were having trouble connecting to people because you weren’t with them long enough. As soon as you felt like you were getting close to them, you were off into something else. The biggest shift that happened in editorial was building longer runs with a character, even when the time of day didn’t make sense for the narrative and didn’t technically work, if you really analyzed it, but it felt right and it felt better. It took a while for us to realize that. I would think, “Oh, God, these three scenes that used to be checkerboarded, all need to go back-to-back.” In theory, if you did a complete forensic drill down on it, it doesn’t actually make sense, in terms of time of day, but emotionally, it makes sense, so you go with it.

I remember the story that some of you might have heard about Godfather II. About a month before the movie was about to be released, they were really worried because it wasn’t working. In the last week, before they had to be pencils down and start making prints, they realized the problem was that they were checkerboarding too much. They ended up expanding the amount of time that they were in each section of the film by double. The version that they almost released of Godfather II, there was twice as much back and forth between the time periods, and they realized people weren’t locking in. They needed to be in longer runs in each of the sections, so that’s what they did. They’d already cut the negative. They had to go back and rebuild the film, at the last minute, and that resulted in what we see today. I remembered that story, and we followed that principle, which saved us.

Image via Max

You watch a lot of reality TV and a lot of true crime. You’ve talked about Below Deck and how the whole point of that show is, if you don’t do anything, it would have been better. Do you feel like that applies to this story?

SODERBERGH: As far as, if you’d done nothing, you’d be better off, that ended up being an actual line that Jim Gaffigan says to Claire on the bench at Washington Square Park. “If you actually do nothing, this will all go away and go back to normal.” That was an expression of my witnessing people in my life, getting themselves into more trouble by making a choice that is demonstrably worse than if they’d literally done nothing. It’s the equivalent for when my emails get backed up, and I’m sure you all have this experience too. I see the number climbing, and then, when it gets to a certain point, I’m like, “Okay, I’ve gotta spend half a day trying to get this down to a number that doesn’t give me a blood pressure spike.” There’s nothing more gratifying than when you realize that thing, six or seven pages back, took care of itself. You’re like, “I never responded, but they didn’t hear from me and they went and solved it.” The goal in life is to figure out which ones those are, while they’re happening, so that you don’t actively make them worse. I think it’s a human problem. Most things can be solved, and our egos think, “Most things can be solved by me.” We don’t consider the, “What if I did nothing,” part of it. The slow version, which I try to employ, moment to moment, in my life and work is, “Well, at least count to 10, before you do that thing, or especially before you say that thing that you feel like you really need to say right now. Just count to 10. If it results in you, a third of the time, not saying that thing, I guarantee you that you’re gonna be better off. The fact that you’re even thinking you should count the 10 means that you probably shouldn’t say this.”

You also watched Atlanta and Fleischman is in Trouble, either right before or as you were filming this. Does seeing your actors in other roles affect how you work, especially when you’re doing reshoots?

SODERBERGH: It absolutely does, and in a way that I think is very helpful. If you’re thinking that the thing that you make just exists in a vacuum, in which there is no other performance by the actor except the thing that you’re doing, you’re deluded. It’s really helpful to know what Zazie is up to and what Claire is up to, so that you have the opportunity to differentiate between those parts because that’s what a viewer is gonna want. A viewer is gonna wanna feel like this is not the same as that. So, I find it really helpful. I didn’t get to see Timothy’s new version of Justified before we started shooting. That’s the way it goes, but I knew he wasn’t gonna be wearing a cowboy hat in our show, so I felt like we were okay.

With that second to last scene between Mel and Sam in the bar, and Sam is really facing her demons with Mel, why did you choose to have those two characters come together and find a similar ground? Did you ever consider a confrontation between Claire and CCH Pounder?

SODERBERGH: No, it was always built that way. The arc of the show was twofold. Mel finally comes to terms with the fact that she’s often her own worst enemy and is a poster child for how there’s maybe some times when you shouldn’t do everything or say everything that you think. And Sam is realizing that she bears real responsibility here, and she needs to acknowledge that. That was always built for those two characters to come together, at that point. But interestingly, one of the sources of debate, that we went back and forth on, was whether to have the scene where Sam goes to her uncle before the bar or after the bar. We always had Louis and Natalia at the end, but we had those other scenes both ways. There was a real going back and forth, and I argued, at one point, that she should go see her uncle after she goes to the bar because then it’s more explicit that she is gonna turn herself in and probably go to jail. She’s heard what the potential ramifications are and she goes anyway to her uncle, to get the information that’s damning to her. I lost that argument, or at least I was convinced by Ed and Casey and the studio, that it felt more satisfying for her to go get the information that’s damning, and then go to Mel and say, “What’s gonna happen to me?,” after that. But we went back and forth. In various cuts, it was one way, and it was the other. It’s a really funny example of why editing is so consistently fascinating. They both worked, but they worked in different ways. And at the end of the day, everybody felt that the way that we have it now was just more satisfying. They loved the transition. It really became about a transition. They loved the transition from the bar to the road in Guyana, and just felt like there was a narrative flow that came through that transition that was satisfying, so I said, “Okay.”

Image via Max

This series deals with crime and many people involved who come from different backgrounds and different levels of privilege. It’s reminiscent of some of the themes you had in Traffic. Did you think about that film at all? In the two decades since that came out, have you’ve evolved on your thoughts on some of these themes, and is this bringing anything new to that table?

SODERBERGH: Yes and no. Traffic seemed a lot easier, in retrospect than Full Circle, in terms of figuring out what the thing wants to be. It happened much quicker, in the case of Traffic. In terms of these larger themes, the sad thing is that these are human issues that are never going away. When we made Traffic, I knew that you could make Traffic every five years because this is never gonna get solved and it’s never gonna go away. And it still hasn’t been solved and it still hasn’t gone away. On the one hand, you have this many states that have legalized cannabis, but these stores are still operating in cash only. They’re not allowed to access the banking system. And so, as a result, when people say, “Well, this isn’t working the way it’s supposed to work, and all the benefits that we were supposed to get from this, we’re not getting,” it’s because they can’t get be part of the normal economic system that every other business of its scale is allowed to access, which is the federal banking system, because the government still views this as something illegal. It’s dangerous. It’s still a cash business. We have a tendency to not be able to get out of our own way, or at least to have an idea, and then before that idea actually gets executed, it becomes so compromised that you can’t really get a sense of whether it was a good idea or not because it’s almost unrecognizable by the time it goes through the legislative process. So, to answer your question, none of the major themes in either of these projects is going anywhere, anytime soon. Especially in New York, there’s a version of Full Circle that you could make every year, that involves two completely different groups of people, up to things that either they shouldn’t be up to, or that are built on foundations that they have not acknowledged are corrupt.

You’ve said that, as of now, you’re not afraid of A.I., it isn’t keeping you up at night, and that it’s just another tool. Do you see any instance where you would make use of A.I., at any point in your filmmaking or storytelling process, or is it not a tool that you see yourself utilizing?

SODERBERGH: Oh, yeah, sure. I’ve played around with it. I think there are ways that it could be helpful. There are just some empirical immutable limitations to it that are never gonna go away, the chief being that it has no actual lived experience. It doesn’t know what it means to have a flight canceled and have to figure out how to get home. At a certain point, that’s a real problem. You have to remember, its only input is data, text and images. That’s it. So, it’s limited by that. It has no body temperature It doesn’t know what it means to be tired. I’ve used it for stuff to play around with, but I’ve never gotten into a Q&A with it. I’d be curious to be interacting with it and go, “Hey, can we take a five-minute break?,” leave, come back, and then ask it, “What were you thinking about while I was gone?,” to see if it had an answer at all, and if it did, what its answer was. What is five minutes? What is four hours to an A.I.? I don’t know. So, I think it’s useful for design creation. I think it’s interesting for a basic way to accumulate a framework. If somebody goes, “I wanna do NCIS in Barcelona,” you load in every episode of that show that’s been made anywhere in the world and you load in all the Barcelona information that you can come up with, and this thing spits out a very frumenty version of how you would do NCIS in Barcelona, that then actual human beings will have to figure out how to make interesting. Let’s say it writes a script and it’s supposed to be a comedy script that ChatGPT has generated, and you say to it, “I don’t know. It’s not funny enough. It needs to be funnier.” And it says, “How?” And you go, “I don’t know, it just needs to be funnier.” What does it do? It’s just a tool. But if you asked it to design a creature that’s a combination of a cat and a Volkswagen Beetle, it can do that. That’s fun.

Full Circle is available to stream at Max.

Publisher: Source link

Strong Week 2 for Horror Movie (Sunday Update)

UPDATE: 2025/08/17 08:08 EST BY BRENNAN KLEIN Weapons Holds Strong With Solid Week 2 Drop This article was originally written Saturday AM and has been updated Sunday AM with up-to-date box office projections (in bold), a full chart, and further…

Aug 17, 2025

Ryan Reynolds Drops Cryptic Tease That Deadpool Could Join AVENGERS: DOOMSDAY — GeekTyrant

It looks like Ryan Reynolds may have just thrown Marvel fans into a frenzy with one cryptic Instagram post.Reynolds recently shared an image of the iconic Avengers logo, but with a red “A” spray-painted over it. The style is exactly…

Aug 17, 2025

Kyle Marvin Interview on ‘Splitsville’

When Kyle Marvin made his first movie, he made one big mistake. “I gave up my day job way before I should have,” he says with a laugh. At the time, Marvin, 40, was working in advertising with his best…

Aug 16, 2025

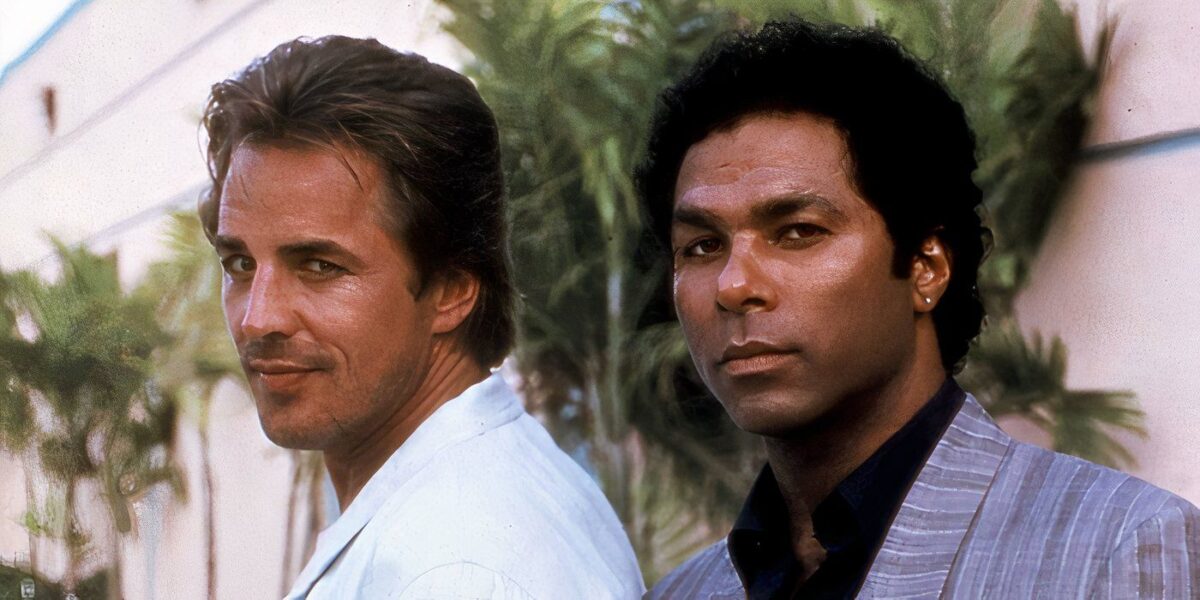

Don’t Worry, the ‘Miami Vice’ Reboot Director Is Treating It Like It’s Star Wars [Exclusive]

The neon lights are shining on visionary director Joseph Kosinski as he prepares to reimagine the iconic 1980s series Miami Vice. The hit NBC show means a lot to Kosinski, so it's important for him that he gets it right.…

Aug 16, 2025