‘The Persian Version’s Maryam Keshavarz on Bringing the Story to Life

Oct 17, 2023

The Big Picture

Director Maryam Keshavarz explores immigrant experiences and the complexities of family relationships in her comedy-drama The Persian Version. The film follows Leila and her journey to discover her parents’ true reasons for moving to America, revealing a long-hidden family secret. The Persian Version tells a universal story with humor and heart, highlighting the importance of personal connections and the power of art to bring people together.

In her upcoming comedy-drama The Persian Version, director Maryam Keshavarz tackles what it means to be an immigrant and a child of diaspora through the eyes of mother-daughter pair Shireen (Niousha Noor) and Leila (Layla Mohammadi). When Leila accidentally gets pregnant after a one-night stand, her already tense relationship with her mother grows even tenser, especially as her large Iranian-American family navigate her father’s health crisis as well.

In an effort to understand her mother better, a mother who struggles to accept Leila’s queer identity, and artistic pursuits, Leila embarks on a mission to uncover the true reason her parents moved to America, discovering a long-hidden family secret along the way. Despite the heavy-sounding premise, The Persian Version tells its story with humor and heart, lending a universality to its distinctly Iranian-American tale.

In this one-on-one interview with Collider’s Arezou Amin, Keshavarz talks about why now was the perfect time to tell this story, and the power art has to make people feel connected. They talk about the choice to not change out the actors as the characters age, the brilliance of the young performers, and the decision to cast Iranian actors from across the diaspora. Keshavarz also shares the personal connections she and her family formed with the story and with the cast, and they talk about the catharsis found in a film like this.

COLLIDER: So, the last time you spoke to Collider you spoke with my colleague Perri [Nemiroff] when you were at Sundance for The Persian Version. Now that it’s a few weeks away from wide release, what has this journey been like for you since winning the audience award, you won the screenwriting award, and now here you are?

MARYAM KESHAVARZ: It’s been amazing. After Sundance, we opened the Munich Film Festival, and it was like this 2,500-person theater, and you just didn’t know what to expect because it’s very culturally specific to America and to Iran. I was, first of all, blown away by Germans being so emotional. They were, like, laughing and crying, standing ovations. It’s an international crowd, obviously, it’s a film festival, but the Germans were very moved by it. But what I found particularly satisfying were all of the different hyphenated people in Germany that came up to me, like Turkish Germans or Vietnamese Germans, Chinese Germans, Iraqi Germans. Actually, that was the way the festival had convinced me to come there because they had written about how important this concept of biculturalism is in Germany at the moment. And I was very moved by the head of the festival’s letter about why we should go there and not to Zurich, for instance. And you know, showing it there and spending some time in Germany, I was really excited to see that this sort of story can translate to other cultures of people who have more than one identity.

Image via Sundance Institute

Why is now, would you say, the perfect time for this “sort of true story?” I know it takes a while, in terms of making a film, but why is now the perfect time for this?

KESHAVARZ: It’s very funny, right? It takes so many years to make something, and then when my film came out, it was like the height of the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement. Obviously, there’s a lot of excitement and hope around these young women who are pushing the boundaries, so it seemed so strangely part of the zeitgeist, just like when I made Circumstance, when I was releasing it. In that film, the young people are dubbing Milk as a way to create revolution, and just as I released that, it was the Arab Spring. I don’t know. I don’t know if, as artists, we have some sort of feeling around things before they happen. These are just actually subjects that have always fascinated me and maybe through some sort of luck they’ve come back around. I find it’s a really important time, both obviously talking about what’s going on in Iran, but more than anything, I think it’s an important time in America to understand about more nuanced stories, fun stories, relatable stories, multigenerational stories about immigrants. Particularly, obviously, we have a big election coming up.

There’s gonna be a lot of rhetoric that tries to demonize and pit Americans against each other, and I hope what this film can do is, you know, maybe people have never met an Iranian-American family, but they feel connected to them. And hopefully, as our own community, we get to see ourselves on screen, be it as an Iranian or anyone from the Middle East, or any immigrant kid, and we can understand that we can aspire to making art, making film, and have that ability to have that voice. For instance, I’m doing this big event in New York; I’m bringing together all the universities to come see the film in one screening from NYU to Columbia to Juilliard, and that was just an idea because I never saw anything like this when I was a student. I think the closest thing I ever saw was maybe The Joy Luck Club when I was in college. I think it’s exciting for people who are in the arts and media to kind of have a conversation about what it means to make personal work, to make personal work that has a mainstream appeal, to talk about collaboration because a lot of the people I collaborated with were also from my community. So, I thought it would be a fun kind of conversation across the different art schools.

I’m going to come back to this idea of culture, but I want to ask, obviously, the 1979 revolution is a fixed point in time in this story, that’s kind of like where the whole thing hinges, but the rest of it is kind of a lot more nebulous. It’s like the 2000s-ish, the ‘90s-ish.

KESHAVARZ: Yeah, although my family came in the 1960s. My family is a little strange in that they came in 1967. So yes, that is the pinpoint, in fact, of the film. It starts talking about that, right? It’s kind of a metaphor for America and Iran are a couple that used to be very close up until the revolution, and then they were at war with each other when they got divorced. So I think that sort of was the perfect way to encapsulate it. And me, I was like the child caught in the middle. It kind of encapsulated what it meant to be an Iranian American immigrant in the ‘80s and ‘90s in America. I mean, we went from our neighbors talking about—I mean, I was very young—but the neighbors talking about, “Oh, the queen of Iran and the king of Iran.” And then when the hostage crisis happened, they were, like, breaking our windows and beating us up. The same people. So it was quite a transition even in the sense of identity. Before, you would say you’re Persian or Iranian, and then for a long time I was afraid to say that. For a while, I would say I was Turkish, strangely! I don’t know why because no one knew where Turkey was. [Laughs]

Then I was like, ‘You know what? I’m gonna get beat up for being…” You’re always faced with a challenge of your identity, so I just decided to embrace what that meant early on in my life and be kind of resistant to letting that bring me down as a kid. My parents really taught us to be resilient and to be proud of who we were, even if that meant we would get our asses kicked. So I have to give it to them. My family, and my mother in particular, really taught me to be defiant in the face of discrimination. They never let us change our names. Mohammad didn’t become Mo or Kareem didn’t become K, you know? We never changed our name. We always kept our names, and we were taught to fight back and to defend what it meant to be Iranian because also, obviously, all of the images these people had about what it meant to be Iranian were very foreign to my experience. So, I think maybe I should credit my mother with my defiance. I think, much to her dismay, that defiance did not end. It continued on at home.

Defiant all the way into an art career.

KESHAVARZ: Exactly.

So, speaking of mothers/daughters, I have to shout out this casting. It was just A+ casting all around.

KESHAVARZ: Thank you.

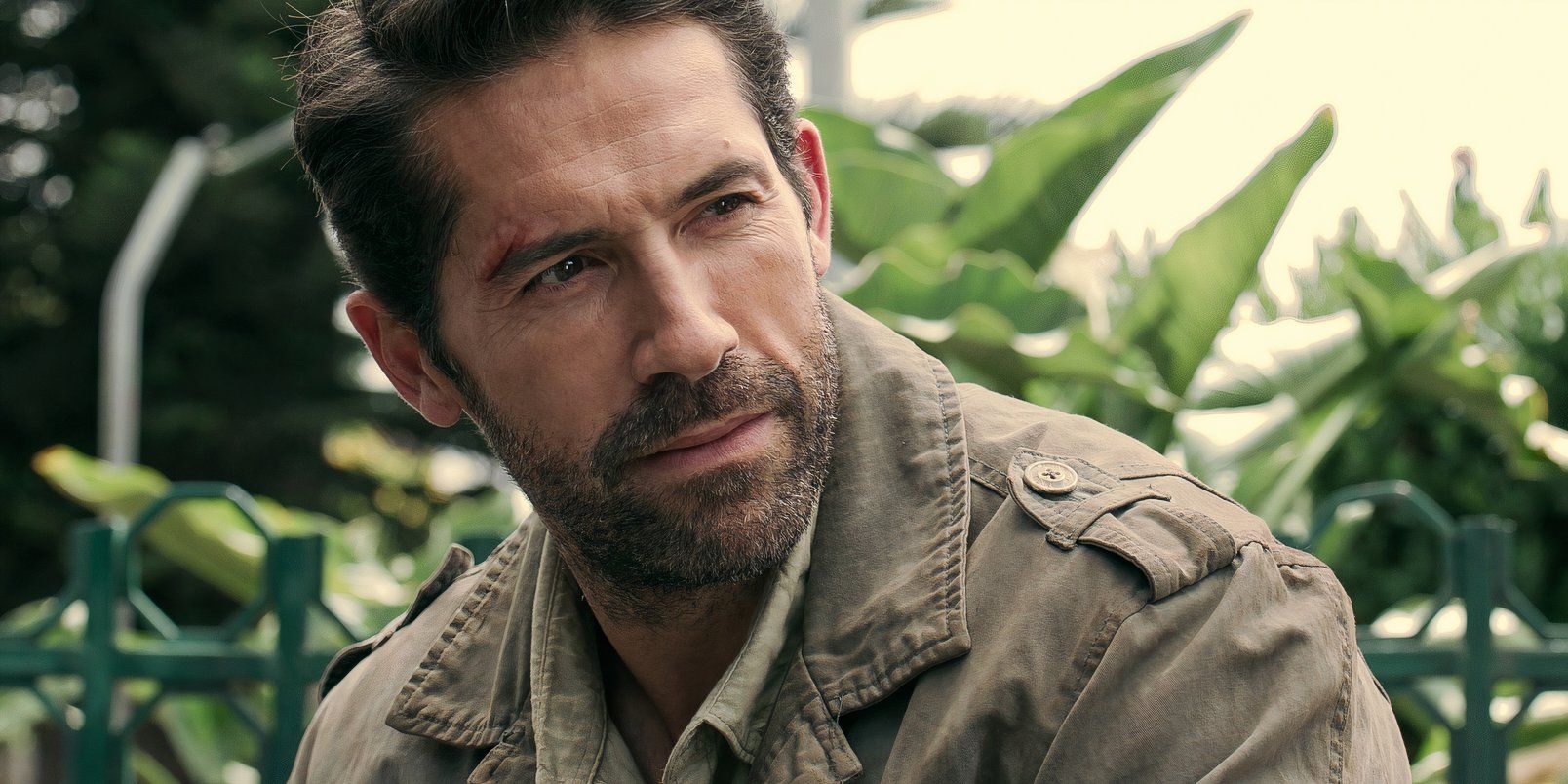

Image via Sony Pictures

I thought it was really interesting that Leila and Shireen, there’s the small child versions of them, but past a certain age, they’re played by Layla and Niousha throughout. What I wanted to know was, was that a choice just because you have these two amazing actresses there already, or was it kind of to convey this visual throughline? Like, despite what Leila sees of her mom, she has always been this young, fierce woman, and visually, we don’t ever lose that.

KESHAVARZ: It’s always a question of casting and how people relate to a character when it’s played by more than one actor, right? So I really did precisely that. It’s like one, I wanted the audience to really feel emotionally connected to this character, and it’s hard to do that sometimes when you switch actors, but also I want to show the fluidity. I look at photos of my mom in her 60s, she doesn’t look much different than when she was in her 20s and 30s. We kind of lose sight that our parents were young when we’re teenagers, or even now, it’s thinking, “Oh my god, I’m my mom’s age when that film starts.” What does that mean? So I think it was very important for a sense of the audience to, as you said, find a throughline, but also to show to the characters that there’s a deep relationship between these two women. They don’t know it throughout the film.

But casting is a major obsession of mine. We found that cast from all over the world, from every country you can imagine. They’re all Persian, hyphen-Persians from the Netherlands and the UK, France, and Canada, the US. But I think what was so important to me when we were casting is that we really have a sense of family. And they did so much work together. They would hang out, the father would take the boys on trips when we were shooting, and Niousha, who plays the mother, not only does she sing the last song of “Girls Just Wanna Have Fun,” but she also choreographed all of the dances at the wedding, the dances at the brownstone. So we really did try to create a sense of family. The actors had met my family, the actresses both had met my mother, so I think it was important for them, also, that they get a sense of this family in the rehearsal. We had not that much of a rehearsal process, but every minute we had, we spent together doing rehearsals and hanging out and eating. We would go out to big meals together on our days off, like the way my family gets together, still, on Sundays. I was even staying with the actor who played my father. Recently in London, I’m shooting a series, and people were like, “Oh, where are you staying?” I said, “I’m staying with my dad,” and they’re like, “I thought your dad died 20 years ago?” I said, “Oh, my film dad.” [Laughs] And that was surreal, too.

My father died when I was in my 20s, right? And so then, I was recently in London directing a show, and he invited me to stay there because my apartment wasn’t ready, so I stayed there for a week or two. You know, I was coming home and having dinner, my dad was making me dinner from set, and we were watching the morning show with my dad, but you know, my dad died so long ago that it was a weird déjà vu where art and life kind of blend.

It got very meta.

KESHAVARZ: Yeah! I got very meta. [Laughs]

On the note of these younger versions of the characters, Kamand Shafieisabet is just so haunting and beautiful.

KESHAVARZ: Isn’t she amazing? She’s a freshman in high school in Iran.

Image via Sony

She’s so good. So she’s in Iran?

KESHAVARZ: She’s Iranian, yeah. I really wanted someone from Iran because I just felt like their exposure, anyone who was in the west, they just wouldn’t have the same sort of innocence that I was looking for. I’ve known her father since I was a kid. We did a main audition process, but he was a student from the north of Iran, and my grandfather was a poet, and he had the biggest bookstore in Iran, so people would come in to buy college books for their university studies. There was this kid, he didn’t have a place to stay. He had come from the north, so my grandfather offered – they have a little back house. He ended up staying in the back house, and he ended up getting married, and until he’d saved money, he had a kid. His kid was Kamand’s older sister, and I always kept it in mind. Originally, I wanted to cast her sister, but she became too old through the whole COVID process. Then, it was just serendipitous because just as I was looking to cast this role, Kamand hit puberty, and literally, she went from this little girl that I knew to this girl who’s taller than me. I just loved her elegance and her understatedness.

So her sister, who was originally supposed to play the role and who had rehearsed, ended up helping prepare her younger sister for the role since she had done all the lines. It became a family affair. Because her parents knew my grandparents so well, they were able to fill in information about all the details about our family and there was like a big sense of getting it right. I mean, it’s a very technically difficult role. She has a monologue where she’s walking. It’s just technically to hit all those marks because people are frozen, right? The camera is moving in, there are no cuts in that, and even a seasoned actor would have a problem. I mean, honestly, she did 18 takes, and almost every single one was perfect. She is just a really natural talent. She knew where the camera was. She had never done acting ever. We just did some exercises. But she was very aware and understated, and she knew how close the camera was, often, to bring down her performance. She just has this quality, she has a timeless essence to her.

She really does. It’s this maturity and gravitas that is way beyond a high school freshman’s lived experience, especially in this day and age.

KESHAVARZ: Exactly. And it’s interesting when my mother met her…My mom came to set, she didn’t want to see the filming, but she wanted to see the rehearsal when we were shooting that section, which was shot in Mardin, Turkey. So she met her in Istanbul before we flew to Mardin. My mom’s a very talkative person, and she was really quiet I said, “Mom, what’s wrong?” She goes, “I never knew how young I was.” It gets me all emotional. “I was struggling my whole life, I just didn’t realize I was a kid.”

And it’s just amazing to have someone who, you know, she was taken out of school, and my dad was a doctor in a village, just like in the story, and she went to a very remote location. Then, you know, just a few years later, she’s in Brooklyn, New York, dealing with everything that comes with that. And living in New York in the ‘60s when my parents came, it was the riots of 1967. That’s when my parents arrived. So it was a whole different world. They had never been on a plane, an elevator, an escalator. She was saying to get on the escalator to take the plane, she didn’t even know how to get on it!

Right, because she’d never seen it.

KESHAVARZ: Yeah, and it was just such an incredible change within a few years, and raising a family in a whole other language, in another culture. I’m surprised we didn’t have more problems when I look back at it. To think that’s only within a couple of decades, this young girl is now navigating a whole other set of cultural rules.

She had to, I guess. You have to do what you have to do.

KESHAVARZ: Yeah. The reason I made this film is my whole life, my family always talked about “aberoo”, “We can’t talk about these things.” But then, a couple of years ago, I said, “Mom, I want to write this story. I want to get your blessing,” and I got all my family’s permission, and I was surprised she said yes. I said, “Mom, why are you saying yes? This is something you never want to talk about.” She said, “You know, it’s time we tell our own stories.” And I think that was a big moment. When she saw it at Sundance, it was a big moment for her to know that we can speak our stories, we can have a place in the landscape and have worth in a way, and not have shame and hiding. And I think part of that comes with being the matriarch. My father’s dead, my grandmother just passed away, she outlived my grandfather by 25 years. So, all the women remain. [Laughs] So they’re like, “You know what? Let’s change the rules. Let’s shake this shit up,” and I appreciate that.

Doesn’t matter what people will say. Let’s just go for it.

KESHAVARZ: Yeah, and that’s a big deal for us. Honestly, it is a big deal in our culture to take that step and to be vulnerable like that. And also to say that our stories are worth being on the screen.

Image via Sony

To that end, the existence in the mainstream, especially North America, because that’s my experience, having a narrative centered around Iranians feels bold just in its existence because I feel like we get forgotten a lot and we don’t really have the chance to tell our own stories. Was there ever a question of watering it down or making it more accessible to a wider audience?

KESHAVARZ: Not really. I think what’s different about this film is, obviously, I love Iranian cinema so much, it’s one of the reasons– I mean, the first female director I ever met was an Iranian woman when I went to the Films from Iran series when I was a student at Northwestern and at the Art Institute of Chicago. I didn’t even know women could be directors, honestly. I only knew that the woman who did Big, which was Penny Marshall, was a woman. I didn’t know that you could be a director. So, I very much appreciate Iranian cinema, and this is not Iranian cinema because, although I go to Iran a lot, even through until recently, until I became banned, and I love the cinema, this is not my influence. It’s not my voice, you know? I have a very different voice.

So I don’t know if I was trying to be mainstream, but I wanted to do something that was Iranian American, that had the elements. And each narrator has a different style or genre in a way, right? Like when the grandmother and the mother are talking. When the grandmother is talking, it’s more like a Western, like a spaghetti Western. When my mother is talking, and she’s in her youth, it’s more like what you consider a classical Iranian film, right? More neorealism. And then when I’m talking, it’s kind of like the craziness of the MTV generation, you know what I mean? I wanted each style to reflect the narrator. So, it wasn’t that I wanted to be mainstream, I never really thought of it that way. I was really just thinking about, “How do we get into the mind of the character so that we can see how they think?”

Because storytelling is so much a part of our culture, as you know, and it’s an art, right? How do we tell stories? It’s hard for, sometimes, outsiders to hear a Persian story because it goes on so many tangents before you get back to the main story. And I really loved that as a kid, you know, sitting in the kitchen and hearing the women, like when I went to Iran, my aunts telling stories, and my grandmother was a great storyteller. So, I really wanted the form of the film to reflect who was telling the story. So it wasn’t so much about being mainstream but really being truthful to who the narrator was in the film.

I should clarify when I say mainstream I just mean available to watch at my theater. Because I so rarely see that.

KESHAVARZ: I was shocked that anyone wanted to finance this film! I was really shocked about the whole process because I don’t think it could have happened maybe 10 years ago that this film would be financed. I really don’t think so. But you know, maybe with Crazy Rich Asians, and Lulu [Wang] did The Farewell, and there were other projects that were coming out. And also, with streaming, the idea is that you don’t only want to be an American film, you want to be a global film. And so this whole idea of what is marketable and mainstream, I think, has shifted so much. Even when I entered film school in 2002 or 2003 for my masters, I had a story not dissimilar to this in some ways, but it just didn’t seem makeable.

So I find it exciting that we’re in a place that this could be considered mainstream. I think it’s kind of funny…I’m so happy and I’m very fortunate this will be in a lot of theaters because of Sony Pictures Classics, and that’s a huge privilege. I mean, it’s a privilege to have a film made. It’s hard. It’s hard to get it in cinemas, and to have that kind of push behind it is really meaningful and I guess it is important to think that this can be mainstream. I hope so. I longed my whole life when I saw Italian American films or Puerto Rican films, or when I saw Spike Lee, or I saw Ang Lee, or I saw Mira Nair, and all these people. Like Mississippi Masala, when I saw those stories, I really wished that we could have our stories up there, you know?

I agree.

KESHAVARZ: So it kind of was a longstanding dream, and I was like, “Well, it’s time to get up off my ass and do it.” [Laughs] This is the thing about life, you never know how it comes about. I was telling a story at a drinks event, and I didn’t know that one of the producers there was from Cinereach. They did Beasts of the Southern Wild, and they’ve done a lot of films that you love. And they were like, “Oh, you should make that into a film,” and they were stalking me. Like, “This is our last offer to pay you to write it!” And my agent is like, “Don’t you want to write it? They’re offering you to do it?” I’m like, “Well, I don’t want to do it as a drama.” And then I said, “I’ll do it if I could do it as a comedy.” And they’re like, “Of course, whatever you want.” They were so supportive of me, honestly, to write this story. And to contain the life of a huge family within an hour and 45 minutes is really hard, but they were supportive through the whole process. I have to say, it was kind of eye-opening and cool to see what translated to people that weren’t Iranian as I was writing the story. I was always shocked, you know, I thought, “Oh, a company is gonna make me want to do it all in English,” and it’s like, no, they want to be authentic. If they speak Persian here, they should speak Persian. I’m really grateful that I was able to make this film the way I wanted to make it. I wasn’t really willing to make it any other way.

Image via Sony

There’s one specific thing I want to ask about, a cultural thing, without going into spoilers. I think maybe you can guess where this is going, but that’s the use of “Arezou” as a name and not just a sentiment in a word. So there is on-screen meaning that the audience can drive from the use of this word as a name without knowing what it means, but if you do know, it means something different. So, tying into what we were talking about earlier, was there a concern that the nuance would be lost, or is it just something that kind of rewards you if you speak the language or know somebody who does?

KESHAVARZ: I think there are a couple of nuggets in the film, if you remember, that you would only get if you’re Persian. Like in the dinner party scene, he goes, “Qazvini-eh?”, and I never translated that. So there are a little couple of nuggets for us specifically. I think the Arezou thing, the name at the end, is important. It’s important to show that there’s a cyclical connection through the generations, be it if we’re conscious of it or not conscious of it, and be that through trauma, or how do you even break trauma? How do you break the cycle of trauma? Maybe by naming it, it can end. And I thought that would be a beautiful sentiment. And then the name is also of personal importance to me. It’s not my daughter’s name, but I’ve always been really attracted to that name for many different reasons. I also had a very big tragedy in my life during COVID, and that particular name, the thought of that name, helped me get through the tragedy. It’s such a beautiful– the meaning, obviously, is so beautiful, and to think that someone, a human, can embody that spirit of hope, and then through the next generation, I think that’s really powerful. It’s a sentiment, also, of the next generation and how we can make change and end trauma and create joy. So, that name was particularly of importance to me.

The first time I heard it in the movie, I burst into very sudden tears because I wasn’t expecting it, and just the context. Then, the second time I heard it was a cathartic cry.

KESHAVARZ: Exactly. And that’s kind of how it functioned for me. And I think even just conceptually this idea that we can have the name of hope or desire, because it has a bit both of those meanings in Persian, onto a child, that’s exactly, precisely what a child brings you when you have it. No matter what the circumstances, being horrible circumstances and beautiful circumstances, you go beyond and there’s this innocence. When you become a parent, it’s like, “Oh, my god.” Now you’re entrusted with a whole blank slate, in some ways, but it still has a DNA of the past, of our past. So, it’s an interesting concept, philosophically at least.

So, to lighten things up a little bit because I made it very heavy…

KESHAVARZ: [Laughs] Let’s talk about dance sequences!

Yes, let’s! What was your favorite sequence to film? Was it the dance sequences?

KESHAVARZ: I don’t know if you’ve been to Iran, but even if you haven’t been to Iran, if you’ve been to any party that has Iranians, what is the first thing that happens? What I was shocked by in Iran is the second you would come by, the people would take off their headscarves and they would just– The headscarves were not even off, and they were already shaking the hips, you know? And that was definitely the case when I was younger. When I grew up in New York in Brooklyn and then later Staten Island in New Jersey, it was such a hard life, especially in the ‘80s. My dad was a doctor in the ‘80s in New York during the crack and AIDS epidemic, but the home and the parties that happened weekly were such a sense of joy, and music and dancing and food were such a way of celebrating life even through very difficult economic times for my parents. Even through really hard social times in New York. I mean, there was so much violence, we particularly faced a lot of violence directed towards us. Our neighbors did because crime rates were the highest in the entire country when I was growing up, murder rates. But I think that that sense of joy, be it in a war zone in Iran or in the war zone of Brooklyn [laughs], I love how music, food, and community can be a respite from the most difficult of times.

I wanted to show that in both cultures. She’s smuggling tapes in after the revolution and during the Iran/Iraq war, which I brought so much music and paraphernalia to Iran. And then, ironically, I would take that Googoosh tapes from Iran because Googoosh was stuck in Iran, and it wasn’t the time of digital downloads and stuff. So my family in Iran had those original Googoosh tapes, and we would bring them from Iran back to America so that our American Iranian community, a lot of them who couldn’t go back to Iran, we would listen to these tapes. So it was kind of an exchange of music, of culture. But throughout both of the countries, what ties us together is, where do we find hope? Where do we find joy even in difficult times? I wanted that to be the driving force of the narrative.

Image via Sony

The smuggling the music was such a specific thing. I lived in Iran for a bit in the early 2000s, and I’m like, “Well, it wasn’t Cindy Lauper, but it was Hilary Duff.” Same thing, in the lining of my suitcase, going, “There’s nothing in there. What are you talking about?”

KESHAVARZ: Oh my god! Because they don’t, you know, when you’re a girl—so you’re a fellow smuggler—they don’t look, right? Because they’re not supposed to touch you and all that stuff. And sometimes I would get scared. Sometimes I’d go to the bathroom before I went through customs and I’d just break the thing and just throw it in the garbage. But yeah, on my body many things could be found. At the time, like, bridal magazines were illegal or Cosmo. If I could get a Cosmo in, I would be the hero of my cousin. You wanted to be the hero when you landed. So I love that.

And that’s the thing, it’s like people think that our communication between the two countries just ended, and it didn’t. It’s impossible to do that. I love that that connection can happen beyond any government control. No government can control a young Iranian woman, be it on either side of the coin.

In any decade. They’ll try.

KESHAVARZ: That’s why when people are like, “Oh, are you surprised with this revolution?” I say, “No, you’ve never met an Iranian woman.” Because all the restrictions really are born by women, obviously us having to cover our hair, all these different things. And you see it in Circumstance, too. The women always found a way to, in my first film, to navigate the controls and the contradictions. And I was always in awe of my cousins. They would break every rule. I would be much more scared than they were, as someone who grew up in the States. I still had a semblance that authority had meaning, and then they didn’t, right? They didn’t believe in the police. All of that was bullshit to them. So, you know, they taught me to be more radical for sure.

So, as we wrap up, then, what do you hope that audiences take away from this film?

KESHAVARZ: I hope they want to hang out with some Iranian families.

Yes. So much fun!

KESHAVARZ: [Laughs] I hope the message of the film is about reconciliation and about finding a way to find joy even with people that we don’t necessarily see 100% eye-to-eye, and how do we have acceptance and how do we keep joy in a landscape that’s constantly radicalizing us and fracturing us and pitting us against each other even within our own families? I hope that people feel a sense of joy and celebration and what it means to be part of a family and be part of a hybrid culture and be part of a multi-hyphen identity. I hope what people leave with in the cinema is joy, and I hope they call their families after and realize that there are many ways that we can be a family. It doesn’t have to be the way that we always think of it. It’s a good question. I’m trying to really think about it. You never really think about those things. I don’t necessarily have those in mind when I make a film, honestly. But I do find that that’s what people have told me, and I do find that very rewarding that people say, like, “Oh, I saw your film, and I called my mom,” or, “I saw your film, and I called my brother.” It made me feel much more at ease with a sense of not having such a fixed identity, you know, more fluidity to it all. But I guess, yeah, acceptance and joy and finding a way to love one another. I hope that’s the message in the end.

The Persian Version hits select theaters on October 20, and opens nationwide on November 3.

Publisher: Source link

Here, We Don’t Believe in Marrying for Love or Alcohol

Editor's note: The below recap contains spoilers for The Gilded Age Season 3 premiere. Julian Fellowes' historical dramas have been capturing audiences' hearts for years, but the latest one, The Gilded Age, is finally back with its greatly anticipated third…

Jun 26, 2025

Reaching for the Stars But Falling Short

Pixar’s latest animated feature Elio marks an ambitious attempt to launch a new kind of space adventure: one that blends a coming-of-age tale with an intergalactic diplomatic mission. Directed by Madeline Sharafian, Domee Shi, and Adrian Molina, and written by…

Jun 26, 2025

Does Maggie Finally Kill Negan?

Editor's note: The below recap contains spoilers for The Walking Dead: Dead City Season 2 finale. The end of Season 2 of The Walking Dead: Dead City has arrived. After a pretty solid first season, the second has had a…

Jun 26, 2025

Station Cosmos Hotel Review: An Incredible Sci-Fi Stay

The Station Cosmos hotel is an out-of-this-world accommodation experience the likes I’ve never seen before as guests aboard a space station and transport themselves into their very own sci-fi movie!Note: Futuroscope kindly offered us a free night as part of…

Jun 26, 2025